It’s 50 years since the first issue of Radical Philosophy was published in 1972. To mark the occasion, we asked a selection of former editors to share their recollections and reflections on their time on the job. We wanted to hear from those involved in the early years, without neglecting those who had participated in subsequent developments. There are memoirs by Jonathan Rée, Sean Sayers, Christopher J. Arthur, Kate Soper and Diana Coole, and an interview with Stella Sandford, by Victoria Browne. There is also an extended interview in this issue with Peter Osborne, the journal’s longest-serving editor, by David Cunningham. (A further interview with Mark Neocleous will appear in RP 214.) They all offer important contributions to a history of RP, with valuable insights into the experiences that founded and sustained it, the ambitions and challenges, the continuities and breaks, not ignoring the crucial, often glamourless and comical practicalities of its production and distribution. Readers will find testimony to the generational solidarity underpinning RP’s exceptional endurance, but they will also discover some of the conflicts and disappointments that are perhaps belied by the image of a half-century old journal. RP has survived because of the extraordinary commitments of its editors, and sometimes despite them.

The selection of perspectives here is obviously partial and inadequate to a comprehensive retrospective. In preparing for this anniversary, some of us trawled through past issues to produce a complete list of editors: we counted 83. And that doesn’t include the dedicated writers who have helped in no small measure to make the journal what it is. The editors we ended up inviting have been gracious enough to expose the personal character of their perspectives, and readers should keep that in mind, not only in considering how they relate to one another but also how they might relate to all those who didn’t get a say on this occasion.

Perhaps the most conspicuous absentees are the current editors. For a variety of reasons, we decided to remain silent or wait for another day. That would be an occasion to describe the major changes that took place since all these former editors left, especially the crisis that the journal went through between issues 200 and 2.01 when it nearly folded. It emerged transformed, as the new production, distribution and financing apparatus that it is today – namely, a freely accessibly online publication, funded through sales of print-on-demand issues and donations, and combined with an archive of issues 1–200 overseen by former editors. This crisis was largely practical, rather than one of ‘ideological direction’, however it was accompanied by a significant change of staff that has had an undoubted impact on the content of the journal since 2016. Whether RP today can still be understood in terms of its founding aims, or perhaps subsequent shifts in those aims, or whether it is now fundamentally different, despite the same name, is a question answered variously by the former editors in this anniversary issue. But, after reading them, it’s a question worth asking anew.

Jonathan Rée, 1972–1994

As far as I remember, my involvement started early in 1971 with a conversation with Tony Skillen, who was a friend of a friend, a lecturer at the University of Kent, an anarchic socialist, and extremely funny. I was a graduate student at Oxford University at the time, and – having previously studied at the relatively free-spirited University of Sussex – I was appalled by the conservatism and complacency of the place. Most of my fellow students seemed to think they were the cleverest people in the greatest department at the world’s top university, and their only aim in life was to suck up to the dons, emulate their tics, mannerisms and put-downs, and follow them into gilded academic careers. I was shocked, and Tony seemed to understand.

Over the next few months there were further conversations, in Canterbury and London, involving – if I remember right – Chris Arthur, Jerry Cohen, Richard Norman and Sean Sayers. The main thing that united us, I think, was a generalised feeling that British philosophy was in the doldrums. It had contrived to isolate itself from the turbulent world around it – from student unrest, from the peace movement, from the politics of anti-capitalism and colonial liberation, and above all from feminism. (The fact that we were all male perhaps confirmed this analysis.) But we knew that we were ourselves victims of the system, having been reared on a one-sided philosophical diet – bits of analytical philosophy and Wittgenstein, with some perfunctory history of philosophy on the side. We were embarrassed about knowing very little – in my case next to nothing – about Hegel, Marx, Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Althusser, Derrida and Foucault, not to mention Simone de Beauvoir.

I was not alone, I think, in thinking that our main task was to liberate ourselves from our brainwashing and – in the idiom of the time – to ‘raise consciousness’ about the arrogance, aggression and narrow-mindedness of the philosophical culture which had shaped us. The idea of producing a regular publication was something of an afterthought, and we envisaged RP not as a vehicle for our favourite philosophical doctrines but as a means of mutual self-education. We thought of ourselves as a ‘collective’ rather than a committee, and strove to make the editorial process open, non-hierarchical and collaborative. After a while some of us became quite proficient in the shared labour of (literally) cutting and pasting bits of shiny typescript onto A1 boards, with the help of scalpels, set squares, drawing boards, drafting machines, Cow gum, Letraset and Rotring pens. The first issue came out in January 1972, and we had no firm expectation that it would continue for more than a year.

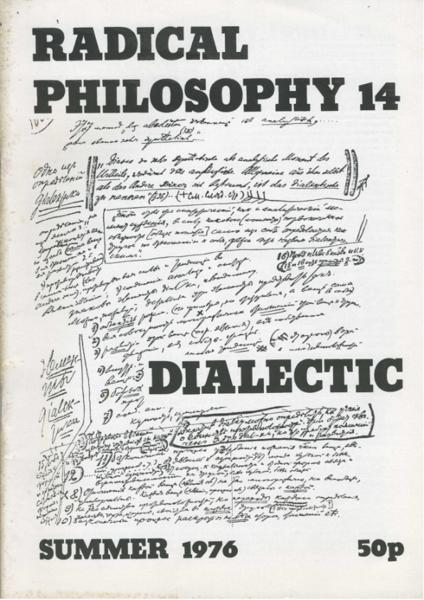

But it went on, and on and on. There were debates, not always good tempered, over Chinese communism, Marxist dialectics, Althusser and Foucault, but as far as I was concerned they were beside the point: the finest exercises in progressive or revolutionary theory were not going to serve much purpose, I thought, if they reproduced the haughty exclusiveness and chilly impersonality of mainstream philosophy. My position was that philosophy needed to escape from the social and intellectual deformations that go with being a modern academic discipline, and I thought that the magazine should model itself not on Mind or Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, nor yet on New Left Review or the even more rebarbative Theoretical Practice, but on the recently founded Spare Rib and Gay News.

In 1978 I resigned from the position of ‘secretary and co-ordinator of the editorial collective’ and contributed a valedictory editorial to RP 20, in which I lamented what I saw as a drift from the attempt to construct a ‘counter-culture’ to the pursuit of ‘theoretical excellence’. But I remained part of the collective, and took on the semi-detached role of reviews editor, until 1993.

Looking back I would describe my involvement in the early years of RP as the most decisive intellectual experience of my life. It opened my eyes to the fact that philosophy – like every other theoretical and literary practice – is not only a body of ideas but also a set of social relations which, for better or for worse, shape people’s lives. After a few years I realised that my approach did not have much resonance within the editorial collective, or much support outside it – that if I wanted to pursue it, I would have to do so on my own. And I came to the conclusion that RP had been captured by the universitarian forces which, as far as I was concerned, it was supposed to resist. That at least is what my memory tells me.

Sean Sayers, 1972–2001

RP was a child of the 1960s. At the time, philosophy in universities was unutterably conservative and complacent. Analytic and ordinary language philosophy, as well as empiricism, of the driest, dullest sort, had a total stranglehold. For young teachers and students this was intolerably blinkered and constricting. An explosion of radical and critical ideas was occurring in the wider world. A group of us in Canterbury arranged a small meeting of some like-minded teachers and graduate students. We decided to create a group to organise meetings around the country and publish a journal, to be called ‘Radical Philosophy’.

Some urged us to reject philosophy altogether as bourgeois academicism, but we were committed to doing philosophy, and to the highest intellectual standards. We wanted to transform philosophy, not to abandon it. We were politically committed to the left and to the reform of the universities. We recognised the central importance of Marxism to radical thought, but many wanted to remain open to other philosophies as well. Some wanted to reject analytic philosophy altogether, others to use it for critical purposes. After considerable discussion, we decided not to commit to a particular philosophy or political line. Rather our aim would be to provide a forum for ideas and debate. Let a hundred flowers blossom! We were determined to avoid jargon and technicality in so far as possible, and to be read by students. Our policy was proclaimed in our ‘Founding Statement’. (See RP 1.)

The first issue appeared in January 1972. We worried that we would be left with boxes of unsold copies, but the journal was an immediate success. We had to reprint the first issue twice. It created enthusiastic interest from the outset. Local ‘Radical Philosophy groups’ sprang up in universities all around the country. These distributed the journal and organised meetings at which the editors often spoke. We also put on some large and lively conferences. A movement developed.

At first, the established world of philosophy was indifferent or positively hostile, but our impact was so great that it could not ignore us. Mary Warnock wrote a foolish piece in the popular weekly, New Society, arguing that ‘radical philosophy’ had nothing to do with philosophy properly so called, and complacently claiming that the commonsensical British were immune to Marxism. However, there were also some supportive responses from established figures. Roy Edgley at the University of Sussex stood out in encouraging us from the outset. Soon it became possible to discuss political issues in philosophy departments, and to mention Sartre, Freud and even Marx.

The main editorial and production work for the first five issues was done in Canterbury by Richard Norman, Tony Skillen and me. Editorial decisions were in the hands of a wider collective that met regularly in London. The success of the journal soon led to demands for the editors to circulate. From issue 6, main control was handed over to Jonathan Rée and a group in London (not without misgivings on my part).

The policy of providing a forum worked well at first, but we soon needed to specify what we stood for positively. We were determined to be open to new forms of philosophy, but we did not want to simply import ideas and jargon from the continent. We fought off attempts to make us into a journal of Foucauldian or structuralist dogma. We were committed to working out our own ideas in our own language. Structuralist Marxism and analytical Marxism were the most influential forms of left philosophy in 1970s and they were discussed critically in the journal. By the mid 1970s some distinctive ideas began to crystallise. Perhaps the most influential was Epistemological Realism. A number of Hegelian Marxists were also closely associated with the journal. (They later formed the nucleus of the Marx and Philosophy Society). With the right resurgent under Thatcher, the left was thrown onto the defensive. The most dynamic forces on the left developed outside traditional socialist political groups in the women’s, peace and environmental movements. All these gave rise to important philosophical debates which provided the main focus of work in RP in these years.

One by one the early editors began to drop out. In the 1980s the journal’s original aims were largely abandoned. Mainstream Marxism was excluded, the focus turned to cultural topics. It became a journal of continental cultural theory. I regretted the direction things were going, but I had no clear alternative to propose nor the energy to fight for it. I was reviews editor in the 1990s and then ceased to be actively involved altogether, one of the last of the old guard.

Philosophy in Britain and in the English-speaking world went through enormous changes in the aftermath of the 1960s. Even a field as sleepy and conservative as academic philosophy was forced eventually to acknowledge and reflect them. RP can claim some of the credit for this. It was not the primary cause of these changes – larger forces were at work – but it provided an effective and influential place where they could be aired and discussed. It appeared at the right place and at the right time with the right means to facilitate them. It was rewarding and exciting to be part of this.

Christopher J. Arthur, 1972–2001

I was involved in the inception of RP. Having become intellectually excited by Marx in my student days, I was extraordinarily fortunate to get a job at the University of Sussex that included teaching an option on Marxist Philosophy – probably the only one in the country – and later introducing one on Hegel. (I joined Sussex in 1965, the same year as John Mepham, another founding member of RP, who taught philosophy of science.) So I naturally joined in the project of RP and the editing of its journal.

RP was originally conceived as an intervention in the stagnant philosophy of the time, as a space for everything heterodox. It soon became dominated by Marxism, but it was just as much an intervention of philosophy in Marxism. It is important to stress that we never discussed – still less imposed – a particular ‘line’, either in philosophy or politics: our approach was very much to ‘let a hundred flowers bloom’. The content reflected what we and our supporters were doing at the time. Jonathan Rée thought most readers valued the reviews above all. Obituaries were also well received. Tony Skillen was keen that we include humour, for instance, the cartoons.

It was hard to figure out who the readers of RP were, especially because many copies were sold through bookshops. I think they were not so much professionally engaged with philosophy, but perhaps from outside the academy, or in other disciplines. Interdisciplinarity interests were characteristic of the left at that time. We attended one another’s conferences. (For example, John Mepham and I were active in the Conference of Socialist Economists.) It was disappointing we never achieved much penetration in the US.

In the early days, the layout of the journal would be rotated between editors in Kent, Sussex and London. My floor in Lewes, and Mepham’s in Hove, would be awash with Letraset etc. I recall John’s young son wanted to help. Eventually a more professional layout was negotiated with specialist production editors from Russell Press. One interesting feature of RP in the early years was that the whole collective never appeared on the mast-head. Instead, the editors listed in each issue included only those present at the meeting to decide (on the basis of internal referees’ reports) what was to go in that issue, thereby taking responsibility for its particular content.

I regard RP as a great success, as it made space for philosophers who were radical to engage not only with each other but with a wider constituency. It is worth noting the existence of an off-shoot of RP, namely the founding of Marx and Philosophy by ex-RP editors (myself, Sean Sayers, Joe McCarney, together with Andrew Chitty) to provide a space for specifically Marx scholarship, although still under the general rubric of philosophy.

Kate Soper, 1974–1998

RP was one of several publications to emerge in response to the student movements of the 1960s and their calls for less insular and conservative approaches in the academy. Its aims were multiple and not always easily reconcilable. Certainly, it wanted to transform philosophy teaching in Britain, to redefine and broaden its remit, exposing in the process the limited and a-historical stance of the Anglo-American analytic tradition and engaging with more continental philosophy. It also aimed to provide philosophers, and intellectuals more generally, with a higher public profile, more akin to that of their continental counterparts. At the same time, it adhered to Marx’s view that philosophy’s role was to change rather than merely contemplate the world, a position deemed absurdly presumptuous by mainstream opponents, but one that inspired a heady engagement with ideas among those more sympathetic, and for which there seems little equivalent today.

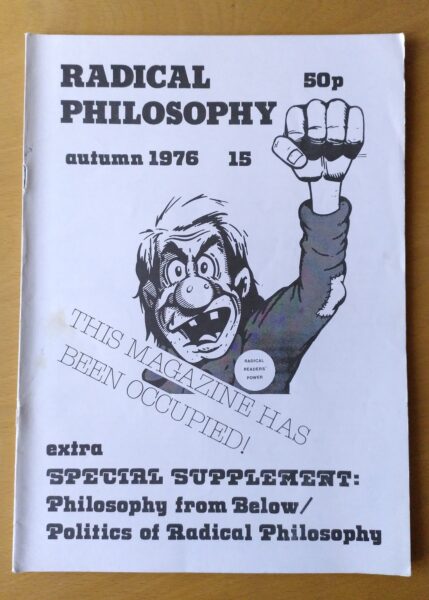

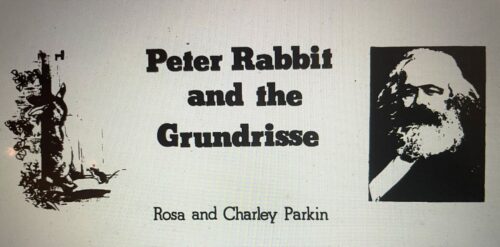

The journal was initially produced and distributed by its editorial collective and their friends – and using methods that by today’s digital standards were primitive. I remember day-long sessions in editors’ houses, where we did the lay-out and pasting up. Errors had to be corrected with bits of Letraset delicately tweezered into place. Illustration was pretty ad hoc. (The images, for example, of the article in issue 11 on ‘Peter Rabbit and the Grundrisse’ were extracted – causing some discontent – from my three year old’s Beatrix Potter books). The first issues were thought too expensive at 35 pence each. But they quickly sold out and RP soon became a bestseller in the philosophy magazine market.

During the first two RP decades, and in the context of the seemingly permanent fixture of the Cold War, left theory was preoccupied with the issue of who makes history and the role of human agency in it. Within RP, this sparked the early disputes between a pro-Althusserian, anti-humanist reading of Marx and the socialist humanism of those retaining allegiance to ‘early’ Marx and the theory of alienation. Subsequently, it was played out in the opposition between structuralist and phenomenological approaches, and was a still lingering concern of the later post-structuralist critiques.

By the 1980s, feminism had become a major influence, there was more writing on gender and identity politics, and on ecological issues. Aesthetics and cultural politics also began to figure more prominently in RP’s pages, and many articles assumed a more scholarly – sometimes even quite scholastic – tone. Some of the political edge was lost in the process, but a flexibility of coverage in the journal has almost certainly been essential to its extraordinary longevity. And the forms of political expression in the earliest issues were, in any case, often crude and contestable in their claims.

That said, one has to applaud the initiative of its founding editors, the energy and imagination they brought to the project, their commitment to a collective ethos and their independence from commercial patronage or sponsorship. It is difficult now to convey what it was like to be involved in the intellectual ferment of that period, with the importance it attached to critical thinking, its confidence in the power of ideas to shape the future, the solidarities and counter-cultural networks it generated, its relative disengagement from more instrumental and careerist concerns. When I think back to the time when the RP groups flourished throughout the country, when RP conferences were attended by hundreds and addressed by academics without a thought for how this would enhance their research profile or university promotion, I can’t help but lament its passing. The world now is arguably more dangerous and unequal than ever before: in many ways it has changed for the worst, and our optimism has proved – at least to date – unfounded. But RP did transform the philosophical climate in this country, and it has managed, against the odds and thanks to the efforts of its successive editorial teams, to continue to shape the philosophical culture of our times. May it continue to continue. I wish it all the best for the next half century.

Diana Coole, 1996–2002

I’d published an article in RP in 1996, entitled ‘Is Class a Difference that Makes a Difference?’ (RP 77), and perhaps that was the catalyst for inviting me to join, although I was also the beneficiary of a decision to expand. When my name first appeared on the contents page, in issue 81, I was one of 17 editors, whereas a year earlier there had only been eight.

I remember feeling incredibly honoured, but also a little intimidated, by the invitation to join some of the 1990s’ most provocative theorists. In 1996 the group included the likes of Peter Dews, Gregory Elliott, Jean Grimshaw, Peter Osborne and Kate Soper, all of whom were publishing important books in the field. RP’s signature, as a socialist and feminist journal, was still relatively straightforward in those days. It spoke not only to a wide, progressive audience, but also to a substantial section of academic social scientists for whom Marxist and (second wave) feminist approaches still retained theoretical primacy. Psychoanalysis was another important aspect of our repertoire. During my tenure, such theoretical identifiers became more complicated and contested, due especially to critiques from poststructuralism and critical race theory that we felt compelled to accommodate.

I’d moved from teaching at Leeds University to Queen Mary during 1996, so it felt apt to join a London-based group that held its meetings in Fitzrovia. We met at the Fitzroy Tavern, a venue redolent of Bohemian lifestyles and a former haunt of writers such as Orwell, Woolf, Shaw and Dylan Thomas. We’d assemble downstairs, monthly, on Saturday mornings before the day’s drinkers arrived. Smoking in pubs was still legal and our discussions were accompanied by the smell of smoke and beer, and the clatter of barrels and hoovers. In summer we’d adjourn to tables outside on Windmill Street.

The enlarged collective was actually quite unwieldy, but we prided ourselves in managing the entire output ourselves and that required all hands on deck. The production process was utterly different from the publisher-based, profit-oriented, anonymous peer review, REF-driven practices of contemporary academic journals. Peter Osborne took it upon himself to design each issue and we often used our own photos to avoid copyright costs. We took it in turn to act as Issue Editor, which would start with making a grid for assigning reading responsibilities to members (we only occasionally sent things out for review). A number of people – maybe five – would be chosen to report on each submission and since there were invariably several experts for any given topic, our discussions about the merits of each piece would be long and profound. I remember those editorial sessions as a master class in continental philosophy. As a rule, everyone looked at all the submissions in advance so they could join in, but woe betide anyone who didn’t have an arguable opinion on an article they’d been allocated.

It was not, in fact, uncommon for every submission to falter before our critical scrutiny and then we’d find ourselves without sufficient material for the next issue. Fortunately, the collective was well connected, so our default would either be to commission pieces or to translate some ourselves, usually from French. In any case, we only included three actual articles as such per issue, the rest comprising of (often in-house) book reviews, reports on special symposia or papers derived from RP’s annual conferences.

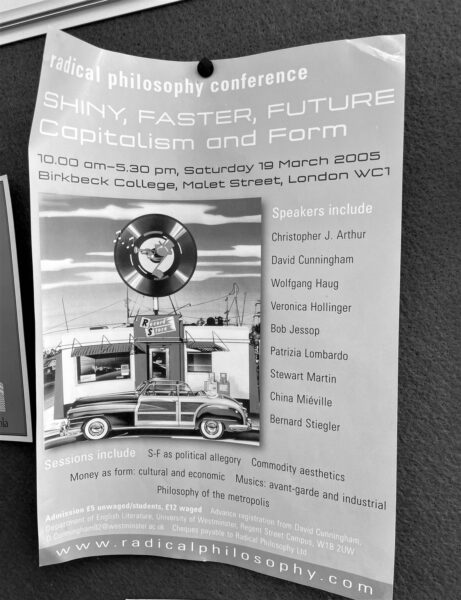

The conferences were an important part of our calendar, both for providing copy and for advertising the journal to wider audiences. We spent ages planning them and choosing the year’s topic. They were always splendid events, well attended thanks to casts of illustrious speakers who generated lively discussions. I remember speaking on one such occasion, in 1996, when the conference was held at SOAS. I joined several leading members of the Women’s Movement who reminisced about their roles in organising the second wave and reflected on its enduring challenges. My contribution, ‘Feminism without Nostalgia’, was published alongside the others the following year (RP 83).

I left the collective in 2002, partly in recognition of the importance for a collective to refresh itself periodically, but also, perhaps, as a result of feeling less attuned to the more cultural, aesthetic direction the journal was taking. My final piece in the journal, ‘Thinking Politically with Merleau-Ponty’, was published in 2001 (RP 108), and my name appeared on the content’s page for the last time in issue 112.

I still read RP and I continued to attend the annual conferences for many years, gratified to find them often being housed at Birkbeck (where I’d moved in 2004, to a department also founded in 1972). It’s exactly 20 years since I left the collective and I still feel incredibly privileged to have been involved with a journal that’s played a unique role in framing essential debates over a turbulent half century. Nonetheless, those days back in the late ’90s now feel like the tail end of an era, when meeting for hours in dingy rooms to discuss the most profound ideas of the day still felt as if it might help change the world.

Stella Sandford, 1996–2016

In what sense is radical philosophy feminist and feminist philosophy radical?

When I joined the Radical Philosophy editorial collective in 1996 it had a strong feminist identity. In my experience this had as much to do with the conduct of editorial meetings and the ethos of the collective as it did with support for feminist philosophy more specifically. When I joined I was a PhD student. There were still relatively few women employed in philosophy departments in universities in the UK at that time. At university, as an MA student, I had been part of a feminist reading group that was also effectively a consciousness-raising group – or at least it was for me. We talked about male dominance in the classroom, the subtle and more overt ways in which male students belittled and tried to silence the women in the classroom, and the marginalisation of feminist concerns in the classroom and on syllabuses. You had to constantly argue for feminist perspectives to be taken into account in institutional contexts. In the RP editorial meetings it was different. It was taken for granted that such perspectives must and should be taken into account. So I think RP was then and is now feminist in a quite general sense.

If you look at the RP ‘Founding Statement’ (RP 1), every aim aligns with the demands of feminist philosophy, although feminism isn’t mentioned there. The statement is about changing the world, making philosophy more inclusive, challenging disciplinary divisions, connecting philosophy to classroom politics, challenging the then-prevailing (and perhaps still dominant) narrow conception of philosophy in the universities. Feminist philosophy has always made these same demands. The hostility towards feminist philosophy in the UK, in the 1970s and ’80s in particular, can probably be explained by the fact that feminist philosophy made these criticisms of philosophy and demanded – and tried to enact – these changes in the discipline. Radical feminist philosophy wasn’t demanding a seat at the table with the same menu and it wasn’t just about how women were treated or whether the climate was hospitable (which it wasn’t). It was about fundamental challenges to the very conception of the discipline. Radical feminist philosophy and feminist theory more generally is critical theory – Kate Soper was arguing that clearly in the late 1980s. Basically, you couldn’t be a radical philosopher and exclude feminist philosophy – it just wouldn’t make sense.

How would you characterise RP’s conception of feminist philosophy?

I don’t know if RP has ever really had a particular conception of feminist philosophy – certainly not as a kind of subfield of philosophy. That idea – feminist philosophy as a subfield – contradicts the idea that the challenge of feminist philosophy goes to the heart of the discipline. But actually it is also the idea of ‘the discipline’ itself that is the problem. The problem is that philosophy is reduced to an academic discipline. To criticise this doesn’t mean to say that everything is philosophy; it’s not that philosophy is the intellectual night in which all cows are black. Feminist philosophy is philosophy done from a feminist standpoint or taking into account feminist concerns, not philosophy with a particular subject matter. Of course it is often going to be about gender oppression but it is striking how much of the early feminist philosophy in RP was also about ecology and the environment. But all radical philosophy must be feminist philosophy, or it is not radical. This is the basic point that socialist feminists and Marxist feminists were making from the beginning of the twentieth century – you don’t get radical anything without feminism. And it isn’t a point about inclusion. It’s a point about the inadequacy of any radical or critical analysis that can’t take feminism into account. Now we can see (which most white philosophers didn’t see then and probably many don’t see now) that there is also no radical theory that isn’t alive to the legacies of imperial and colonial histories, and that can’t take critical race theories into account. But looking back it has to be admitted that the feminist philosophy in RP has been overwhelmingly white feminist philosophy. It wasn’t until the past few years that any attention has seriously been paid to addressing that. We should have done better in that regard.

Can you comment on the contribution feminist philosophers have made to the journal’s output and ethos since it was founded? And do you think the journal has had an impact on feminist philosophy in the UK, and UK philosophy more generally?

I think it is fair to say that in the 1970s RP was the only philosophy journal in the UK committed to feminist philosophy. The UK Society for Women in Philosophy (SWIP) was formally founded in 1989 and based on informal networks in philosophy that had been around since the 1970s, but their journal – The Women’s Philosophy Review – was first published in 1993 (succeeding the Women in Philosophy Newsletter, also begun in 1989). For a good while the memberships of the SWIP executive committee and the RP editorial collective overlapped, with different people (myself included) at different times part of both. Jean Grimshaw and Alison Assiter were founding members of SWIP while they were members of the RP collective. There were few articles by women in RP until the early 1980s, although Kate Soper’s, Joanna Hodge’s and Jean Grimshaw’s names appeared regularly in commentary and reviews sections from the beginning. The first special issue (I think there have only ever been three special issues) was RP 34 (Summer 1983) called ‘Women, Gender and Philosophy’. After that, from issues 35 to 70 (roughly 1983-1996) it is remarkable that there is almost always feminist content in every issue. There was no other general philosophy journal of which this was true, and even now it is only true of journals like Hypatia that are dedicated to feminist philosophy. From RP 61 (Summer 1992) RP bears the subtitle ‘A Journal of Socialist and Feminist Philosophy’. So there was definitely a distinct feminist bulge in RP in this period, and given that there were very few places where people could publish feminist philosophy it did play a significant role in promoting feminist philosophy in the UK. This was also due to the influence of prominent feminists who were not part of the collective but were close to people (men) who were. Lynne Segal, for example, was never a member of RP but is an important part of its history and was influential in its increasing feminist orientation. Did this have an effect on philosophy more generally? That is difficult to say. Certainly some feminist philosophy is more accepted now. But what kind of feminist philosophy is acceptable to the mainstream? Is it the kind of radical feminist philosophy that we were talking about earlier? I fear not.

Was there a clear collective sense of the kind of work you wanted to publish during your involvement with the journal?

In the late 1990s and early 2000s there were often disputes – sometimes quite angry arguments – in editorial meetings about whether particular submissions ought to be published. To be honest, by the mid-2000s, I think a lot of the time we knew what kind of thing we wanted to publish but people weren’t writing it. Or, if they were writing it, there was less and less connection with philosophical analysis, because there was less and less philosophical work engaged with the kind of political questions RP wanted to ask. I’m afraid this is true also of feminist philosophy.

By the time I left the collective most of the journal content was commissioned; we were publishing very few ‘cold’ submissions. This was partly due to the increasing conservatism of research in universities in the UK. I mean, the RAE (now called the REF) (which Sean Sayers criticised back in RP 83, 1997) seemed to be leading people to be pressured into publishing in the ‘right’ journals, and RP was very definitely the ‘wrong’ journal in this respect. Journals began to be ‘ranked’ more or less officially, and people were – they still are – pressured by their institutions to publish in the high-ranking journals.

The greatest irony is that RP has probably always had a far greater readership (by which I mean people actually reading the journal, not necessarily distribution) than any other contemporary philosophical journal. If you want people to actually read your work, publish in RP. If you want institutionally-approved kudos and mainstream legitimation, go elsewhere.

You were a member of the editorial collective from 1996 to 2016. Can you recall any particularly memorable situations from this period?

For me the 1998 conference on ‘Philosophy and Race’ is particularly memorable. Charles Mills was one of the speakers. I confess that at the time I didn’t realise quite what a big deal that was, even though I invited him. I talked to him about the murder of Stephen Lawrence (in 1993) and he helped me to understand how and why it was so important that Doreen Lawrence had become a public figure in the UK. We published a special issue on ‘Philosophy and Race’ (RP 95, May/June 1999) with some papers from the conference. At the conference Isaac Julien called me out about the special issue. Screen had published what they called ‘The Last Special Issue on Race’ in 1988 (Vol. 29, no. 4) in which he and Kobena Mercer had described it ‘as a rejoinder to critical discourses in which the subject of race and ethnicity is still placed on the margins conceptually, despite the acknowledgement of such issues indicated by the proliferation of “special issues” on race in film, media and literary journals’. I accept the point, but the fact was that, to my knowledge, there had been no special issues on philosophy and race in the UK up to that time. Philosophy was – still is – so very far behind in the humanities and the social sciences when it came to understanding its own implication in histories of colonialism and racism, and how its white-washed view of its own history perpetuates this.

But honestly, the whole period was absolutely formative for me. I saw what a collective intellectual project was for the first time which I had never previously seen in my university experience. Or perhaps it allowed me to recognise collective intellectual projects when I saw them, because many of the philosophy departments in the polytechnics had something of that about them in the 1980s and 1990s, and certainly that was how a bunch of my colleagues saw things at the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy at Middlesex University and now at Kingston University. RP was a fantastic mixture of intellectual work and sociality. We had meetings in a downstairs room of a pub in Bloomsbury and afterwards we went up to the pub and often continued there for hours. It was really very, very enjoyable, and that was not a peripheral aspect of it, it was part of the collectivity itself. I have to mention that I didn’t have children then, because once childcare became an issue sociality suffered. This aspect of social reproduction is still one of the biggest issues for feminist politics. Crèches can be great but not all children are happy to be left for a day with adults they have never met before. Crèches are an ad hoc solution to a problem whose resolution requires far greater social change. One time I had to bring the children with me to a meeting, and afterwards we had dinner with members of the collective in an Italian restaurant. It was really good. If an intellectual organisation can’t accommodate children when it needs to, it is not radical.

What do you consider RP’s project to be, and to what extent do you consider it to have succeeded?

RP’s project has probably changed. When I joined I was fully on board with the project as I understood it then to be: to challenge narrow disciplinary conceptions of philosophy, to make explicit the political stakes in all philosophy, to render philosophy relevant and useful to radical political projects (especially for me, at that time, feminist political projects). It definitely succeeded in providing an alternative to the existing, mostly conservative philosophy journals. It definitely succeeded with its content – the archive is extraordinary. I think RP succeeded on its own terms. But it alone could not face down the institutional and national policy changes in the UK that have tended to render philosophy in the universities more homogenous (bye, bye continental philosophy …), more subject to market imperatives, and more abjectly in thrall to making a mark in ever more shallow, popular forms and to having ‘impact’ as it is defined by Tory governments (which doesn’t stop Tory governments hating it more and more anyway). In this sense la lutte continue.