Most branches of philosophy and many other disciplines in the humanities and social sciences studied in the anglophone academy draw on texts written in languages other than English and therefore rely on the products of translation, especially translations of historical, European philosophy. However, surprisingly little philosophical attention has been paid to the role of individual translators in mediating and relocating philosophical narratives across cultural and linguistic boundaries. The blind spot may be attributable to a long-cherished philosophical aspiration to evolve a universal, purely rational or scientific language and discourse which are, perhaps implausibly, immune from such translational and/ or translatorial mediation and dislocation. Since it is situated outside the philosophical mainstream, the now well-established interdiscipline of translation studies[1] may be able to shed light on an unjustifiably neglected corner of philosophical enquiry. With reference to a topical case study of the English translations of Hegel’s Phenomenology, [2] the present article draws on textual analysis and social psychology to raise awareness about the manner in which translators of philosophy engage demonstrably, through what I will call their translatorial hexis3 – a post-Bourdieusian manifestation of the translator’s will to power – in the linguistic and social practice of re-describing and disseminating putatively universal philosophical truths.

The philosophical study of translation has traditionally focused more on analysing the metaphor of translation or investigating theories of hermeneutics rather than considering translators, translated texts and/or their relationship with such analyses. [4] Translation theorists have also tended to start from cognitive-semantic or hermeneutic perspectives when discussing translation and philosophy. [5] Such theoretical approaches have already prompted broader interdisciplinary discussion of translation and philosophy, which this article seeks to continue. [6] However, when philosophers themselves refer to translations of philosophical texts, it is often merely to criticize their lack of consistency, accuracy, rigour and/or fidelity to the source text or to praise their style or readability. Contemporary writers on continental philosophy sometimes adapt the text of published translations either to fit their own interpretation of the text cited or because they claim that the published translations are inadequate to the task. [7] Perhaps unwittingly, such responses to translated philosophy promote an oversimplified understanding of the nature of translation and the role played by translators in mediating textually encoded ideas. They imply, unrealistically and contrary to the theoretical considerations of translation mentioned above, that good or accurate translations can offer neutral and unmediated access to the ideas of the originating author[8] or that translators of philosophical texts should be governed by an attitude of (greater) subservience[9] to the assumed intentions of the source-text author and/or the convenience of the reader. In contrast with this trend, the present article aims to encourage a broader, sociologically grounded appreciation of what is involved in translating philosophical texts which draws attention to a hitherto under-recognized human dimension to the translation of philosophy, described here as the translatorial hexis.

The article argues that the anglophone translations of Hegel’s Phenomenology, including the new Pinkard translation which is taken as an example here, form an integral part of the historical corpus of literature on Hegel and embody, at a micro-textual level of analysis, culturally determined rivalries central to the discussion of philosophy and translation. Translations should not be thought of merely as tools. Seeking to understand the translations in a broader contextualization can contribute to the crucial interpretive and philosophical tasks, for example, of identifying what Hegel actually claimed in his works, distinguishing this from what others have written about Hegel at different times, in different languages and under different social and political conditions, distinguishing between claims Hegel was entitled to make, for example, within the terms of his mature system and those which seem to fall short of this criterion[10] and finally recovering from this analysis what is still valuable to philosophers and others today. The translators of Hegel have all, in different ways, been deeply engaged in these tasks, each exhibiting a different translatorial hexis, with a different portfolio of masterful and subservient dispositions.

Google Geist

The idea of a translatorial hexis is a development from Bourdieu’s theory of habitus, field, capital and symbolic power, which is familiar in sociological approaches to translation studies. [11] It provides a theoretical tool for analysing and contextualizing differences between the Hegel translations on the basis of what Bourdieusians call a ‘radical contextualisation’. [12] It can be compared with but goes significantly beyond the concepts of translatorial ‘voice’ or ‘presence’ or ‘agency’ invoked in translation studies to explain the translator’s ‘visibility’. [13] In his sociology, Bourdieu stresses the interdependence of apparently free (individual) agency and (institutionally) structured distributions of power in the social space. Bodily gestures, for example, of dominance or subservience, mimic or reproduce social structures. The translatorial hexis denotes the symbolic stance of a translator, articulated as an empirically discernible set of principles and expectations guiding translatorial choices, which is, to a greater or lesser extent, determined by the background of oppositions defining a specific field or sub-field within the social space surrounding the translator. The concept of a translatorial hexis also resonates with Bourdieu’s later work[14] in which he analyses the ‘elevated’ writing styles of philosophical texts and their translations, especially Heidegger. Bourdieu’s analysis focuses on the ‘conflict of the faculties’, especially in French universities from the late 1960s onwards, challenging the ivory-tower dominance of philosophy in French universities. By analogy, the translatorial hexis is construed as a textual embodiment of translatorial dispositions which relate to the distribution of various forms of capital or honour within the academic sub-field of anglophone Hegelian philosophy. Oppositions in the sub-field are reproduced by oppositions in and around the text.

Significantly, however, the translatorial hexis contrasts with the ‘subservient’ translator’s habitus discussed in a seminal translation-studies paper by Daniel Simeoni that refers especially to professional translators, who are constrained to make themselves seem invisible by comparison with the source-text author. [15] The translatorial hexis expresses the translator’s linguistic prowess and authority over the semantic content of the translated philosophical text. Like Bourdieu’s use of the term hexis in his early ethnographic work in Algeria, [16] the translatorial hexis is physically embodied, but here it is encrypted symbolically in the text and paratexts to the translation. [17] Accordingly, Pinkard’s translatorial hexis is discernible in the numerous philosophical, ethical and political commitments encoded not only in the wider context of his philosophical writing and in his translator’s notes but also in the minutiae of his lexical choices and the translational norms underlying the translated text.

One way of visualizing the field dynamics which form the historical background to the contextualization offered here is to think of zooming in with an imaginary software application such as Google Earth towards a historical, ideological map of the world at the time of each translation of Hegel’s Phenomenology, say, in 1910, the date of the first English translation of Hegel’s book (Baillie’s), in the late 1970s while A.J. Miller was working on his translation, and in 2008, the copyright date of Pinkard’s first online draft. At one level of magnification, we can see the world political situation, characterized by the oppositions of international power and cultural interpenetration; as we zoom in closer, we see party-political, class and personal competition and conflict; closer still, microscopic rivalries within the sub-field of anglophone Hegelian philosophy between different readings of Hegel’s philosophy, articulated through philosophical books and articles; at the closest resolution (perhaps we can think of the Google street-view function), we see individual words and spellings in the translations which also participate in these rivalries as an embodiment of the translators’ irrepressible, conscious and unconscious will to power.

At this global level, the relevance of Pinkard’s new Hegel translation might be contextualized, on the one hand, with reference to Hegel’s indirect, historical associations with communism, as an influence on the thinking of Marx, Lenin, Mao Zedong and Althusser, but, on the other hand, with regard to the charges of Eurocentrism and protestant Christian elitism levelled against Hegel. [18] Such accusations (or myths), which mimic the older left-Hegelian/rightHegelian divide, often relate to the Phenomenology, especially to the famous, master/slave dialectic and such tantalizingly contested concepts as Geist [mind/ Spirit] and aufheben [sublate/abolish]. Accordingly, Pinkard’s American, democratic-liberal reappropriation of Hegel in his own philosophical writing wrests Hegel away from the communist camp by explaining that the association of Hegel with communism was based, inter alia, on Marx’s misunderstandings of Hegel. [19] By association, the translation and the translator participate in the wider discussion of world politics because the text already participates in such discourse.

Focusing more closely on Pinkard’s world, twentieth-century communitarianism, which is historically associated with the philosophy of Aristotle and Hegel, had its roots in the work of Anglo-American political philosophers Alasdair MacIntyre, Michael Sandel, Charles Taylor and Michael Walzer, who challenged the vision of liberalism presented in John Rawls’s book A Theory of Justice. [20] Their challenge can be summarized with reference to two central themes. First, the version of liberalism presented by Rawls in the 1970s seemed to these philosophers to require the acceptance of universal principles which must be accepted by everyone because they are universally right, regardless of differences between people. Communitarians rejected this view, arguing that political and legal principles must be derived from the internal logic (or Geist/ spirit) of particular communities and may therefore vary from culture to culture. Second, communitarian philosophers argued that Rawlsian liberalism placed too much emphasis on individual freedom, especially freedom of choice and the autonomy of the self, at the expense of social values (Geist and Sittlichkeit [ethical life]) inherent in the concept of community. The communitarian view is therefore also theoretically opposed to the emphasis on individual rights associated with libertarianism. [21] While the philosophy of Kant is particularly associated with the history of liberal thought and the (deontological) ethics of individual rights and duties investigated by Rawls, Nozick and many others, certain aspects of Hegel’s philosophy – especially according to Pinkard’s 1990s’ non-metaphysical reading of Hegel which placed emphasis on mutual, democratic recognition between individual self-consciousnesses (‘social union’) and on the ‘sociality of reason’ [22] – provide precisely the critical and theoretical move forward from Kant required in support of the communitarian position. Pinkard’s socio-political, analytical style, as developed in his philosophical writing, equips Pinkard the translator for the challenge of ‘reconstructing’ [23] some of Hegel’s more elusive, ostensibly metaphysical concepts, such as Geist (mind/spirit]) and aufheben (sublate) in terms accessible to their new, anticipated readership of modern, anglophone students and teachers of philosophy.

Zooming in closer on the Hegelian scene in the midto late 1990s, the distinction between ‘traditional metaphysical’, ‘non-metaphysical’ and ‘revised metaphysical’ readings of Hegel characterized the sub-field of anglophone Hegelian philosophy in the period leading up to Pinkard’s translation of the Phenomenology.[24] The traditional metaphysical interpretations of Hegel emphasize the monistic near-identity of Hegel’s Absolute Spirit with some Christian conceptions of God and therefore seem to draw on a pre-Kantian or pre-critical conception of philosophical metaphysics. The group of nonmetaphysical readings sees the importance of Hegel’s philosophy in its development of Kantian critical philosophy in new directions which reject some or all of the metaphysical claims about ‘Absolute Spirit’ and are thus made relevant to political and social theory in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. A set of revised metaphysical readings reasserts the essential metaphysical (ontological and logical) nature of Hegel’s philosophy while modifying some of the more extravagant metaphysical claims of the traditionalists and incorporating some of the non-metaphysical discourse. In the 1990s, Terry Pinkard was clearly associated with the non-metaphysical position.

Contra polemic

The defining sense of opposition across the subfield at this time is exemplified by a public dialogue between Frederick Beiser and Pinkard in which Beiser challenged the dominance of the non-metaphysical position in the mid-1990s. Beiser published a negative review in the Bulletin of the Hegel Society of Great Britain of a Festschrift for Klaus Hartmann which had been co-edited by Pinkard. Hartmann was one of the founding figures in the history of the nonmetaphysical readings of Hegel and, significantly, also one of Pinkard’s early mentors. The review provoked a response from Pinkard and a further response from Beiser. [25] Beiser concludes his initial polemical review as follows:

My final verdict on Hartmann’s interpretation is that it is profoundly, indeed blatantly, anachronistic, forcing Hegel into the mould of modern preconceptions, now dated by post-modern standards. It does not mark an advance but a decline in Hegel scholarship, a deep drop in standards of historical accuracy and philosophical sophistication. There is nothing to be lost, and much to be gained, by simply ignoring it. [26]

Overall, the review offers a detailed but scathing criticism of the non-metaphysical position. In Pinkard’s response to Beiser, ‘What is the NonMetaphysical Reading of Hegel? A Reply to Frederick Beiser’, Pinkard specifically addresses Beiser’s polemical style. Beiser’s article was entitled ‘Hegel, a NonMetaphysician? A Polemic’. The question mark here indicates a rhetorical question expressing astonished laughter at the absurdity of such a suggestion. The term ‘polemic’ suggests Beiser’s aggressive, honourseeking philosophical hexis. Pinkard begins his reply by acknowledging that Beiser has raised interesting questions in his criticism, and continues:

Beiser’s tract is also a polemic, a rare form of philosophical writing nowadays, which lends it a certain dash that is sometimes lacking in the form of the impersonal academic article. If nothing else, Beiser’s polemic certainly sounds much more like the real, historical Hegel writing about, for example, J.F. Fries than anything any so-called non-metaphysical Hegelians typically do. [27]

This comment gives a good insight into Pinkard’s own contrasting and more complex hexis. Pinkard concedes that the modern ‘impersonal academic’ style sometimes lacks excitement by comparison with the older, rhetorical style of the polemic and also admits that Beiser’s style may ‘sound’ more like the ‘historical Hegel’ than the style of modern philosophers. However, these two comments are more subtly damaging than they may at first seem. Pinkard relegates Beiser to an old-fashioned and perhaps overinflated generation, the generation embodying what Bourdieu described as the ‘elevated’ style. Moreover, Pinkard suggests that this elevated style is ultimately hollow. The arguments may ‘sound’ convincing, but real (modern) philosophy has to do more than this. Pinkard’s hexis in this philosophical standoff is based on his invocation of the modern and the impersonal, the cool and analytic. Later in his reply, Pinkard gives his own concise definition to clear up ‘the fuss about the non-metaphysical reading’. [28]

According to Pinkard’s account, if the selfgrounding nature of Hegelian logic is taken to be the central part of the system, some of Hegel’s statements about religion and history, statements such as those in the Phenomenology relating to the historical (evolutionary) progression of various religions towards the most developed (‘highest’) state of Protestant Christianity or the (subordinate) role of women in civil society, [29] may not be justifiable in Hegel’s own terms. That is, some of Hegel’s apparent judgements may not follow consistently from the logic of his system so construed. Pinkard mentions the specific point regarding the superiority of Christianity over Judaism.

But the crucial question remains: how much can Hegel rightfully assert on the basis of his own principles? It is relatively clear, for example, that Hegel thought that Christianity was a ‘higher’ religion than Judaism; there’s probably little doubt that he held that view. But many (myself included) want to know if that really follows from Hegel’s views, or if it is more of a display of something that Hegel wanted to justify but actually could not, perhaps a reflection of his times but not a necessary consequence of his thought. [30]

Pinkard’s defence of the non-metaphysical approach at this time thus ultimately relies on his (and his readers’) analysis and evaluation of Hegel’s claims with regard to their logical necessity. One intractable, question-begging step in this argument is that modern anglophone readers can only evaluate Hegel’s claim to logical integrity indirectly through their own necessarily selective reading of the various translations and the vast body of secondary literature in English. Even for those who read German, coming to understand and discuss Hegel’s ideas is necessarily a diffuse, probably multilingual and certainly multitextual project.

Lexical patterning

Hegel’s Die Phänomenologie des Geistes was published in 1807.[31] It was originally translated into English by James Black Baillie in 1910 as Hegel’s The Phenomenology of Mind. The A.J. Miller translation and the new Pinkard translation both translate the title as Phenomenology of Spirit. The Phenomenology is not simply or directly about the experience of human consciousness, as its title suggests. In addition to its central concerns with ontology, epistemology and logic, it has significant implications for historiography, ethics and ideology, especially with reference to how different cultures have tried to understand the phenomena of consciousness, mind and spirit, and the historical and social development of rational mindedness. In each of the six main chapters, Hegel invites the reader to investigate ‘speculatively’ how different forms of Consciousness, Self-consciousness, Reason, Spirit, Religion and Absolute Knowing have evolved through European history and how each of these historical approximations has failed through the shortcomings of its own self-understanding. In spite of such negative findings, there is also a positive progression through the book towards absolute knowledge, a state which itself, however, merely introduces the reader to the need for radical, ‘scientific’, philosophical enquiry. [32] As already mentioned, the most famous passage, which occurs in the Selfconsciousness chapter, examines the recognition of mutual interdependence between the opposing states of self-consciousness of the ‘master’ and the ‘slave’. Hegel’s metaphor resonates through much of the subsequent discourse in the humanities, not least in sociology, translation theory and intercultural studies. Many books on the Phenomenology have been published in English. Pinkard’s The Sociality of Reason is controversial but by far the most comprehensive recent study. Pinkard has also published a major biography of Hegel. [33]

The elevated, literary style of English found in the earlier translations of Hegel[34] can present an obstacle to students familiar with more analytical philosophical styles. Even for those who understand some German, the earlier translators’ apparent dis regard for terminological consistency in the translation of key terms makes it difficult to read the translated text with the kind of close cross-reference to the German source text required for advanced study. In the introduction to the 1931 second edition of his translation, Sir James Black Baillie explains that a translation of a work of such profundity as Hegel’s Phenomenology ‘must necessarily be in large measure an interpretation of the thought as well as a rendering of the language of the text’, [35] but he provides readers with few clues as to where the boundaries between interpretation and intertextual equivalence might lie. Lexical patterning found in this translation provides convincing evidence that Baillie’s apparent inconsistencies are, in fact, part of his interpretation rather than instances of carelessness. [36]

Baillie’s translations of Geist, for example, might initially seem to be merely inconsistent. He appears to switch arbitrarily between mind, spirit and Spirit throughout the book. The 1910 first edition of Baillie’s translation was published in two volumes. In a footnote on the first page of the second volume, at the beginning of the chapter entitled Spirit, Baillie explains his strategy as follows:

The term ‘Spirit’ seems better to render the word ‘Geist’ used here, than the word ‘mind’ would do. Up to this stage of experience the word ‘mind’ is sufficient to convey the meaning. But spirit is mind at a much higher level of existence. [37]

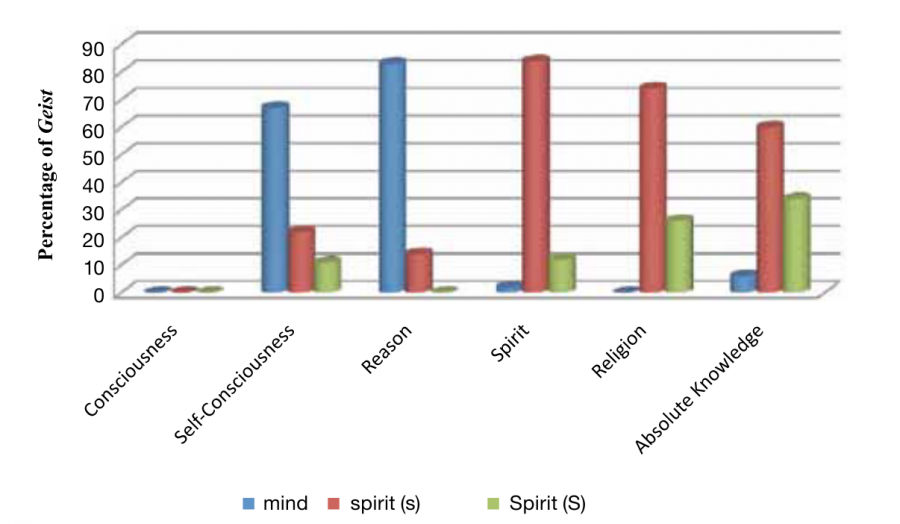

A more detailed analysis of Baillie’s translations of Geist in the six main chapters of the book shows the following ‘lexical patterning’. The bars represent percentages of the number of times Geist is translated as mind, spirit or Spirit with a capital ‘S’ in each chapter. If we concentrate only on Hegel’s usage of the noun Geist and Baillie’s translations, we become aware of a translatorial structuring of this cohesive chain running through the text. I have argued elsewhere[38] that such patterns are microscopic traces of Baillie’s engagement with the rivalry between Absolutist and Personalist versions of British Idealism. Baillie’s patterned translations of Geist challenged the then orthodox monistic interpretation of Hegel’s Spirit as an immutable One suggesting stages of the human journey – from blue to red to green in my graph – towards full spirituality.

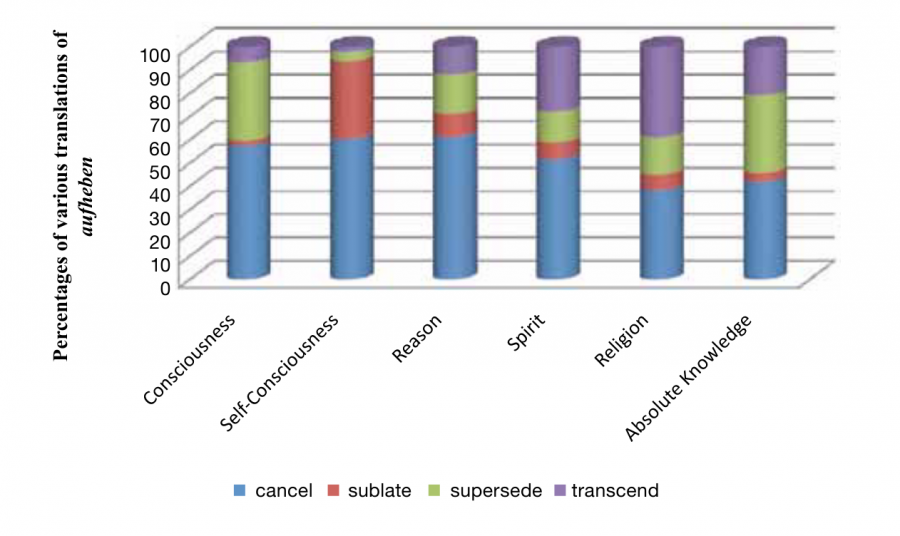

Patterning can also be found in Baillie’s apparently inconsistent translations of the term aufheben (sublate). Baillie used 13 different English verbs in his translation of the 308 verbal and nominal occurrences of aufheben found in the six main chapters of the book. He also used pairs of verbs, such as cancel and transcend, especially in the later chapters. The following table clearly shows cancel as Baillie’s preferred translation, but with sublate in the Selfconsciousness chapter and transcend in the Religion chapter as the second favourite. Supersede is second favourite in the first and last chapters.

In his translator’s foreword, written in 1976, A.J. Miller indirectly criticizes Baillie’s work as follows: ‘I have done my best to steer a course which, while avoiding loose paraphrase, departs at times from a rigid consistency.’ Miller’s translations of Geist are certainly more consistent than Baillie’s. Faced with his predecessor’s three options, Miller chose Spirit. He therefore removed Baillie’s lexically mediated strengthening of Hegel’s undeniable narrative of progress towards Spirit. Miller’s foreword also refers to his use of capitals in the translation. ‘I have been sparing in the use of capitals and, in general, have only used them for terms which have a peculiarly Hegelian connotation. The German Verstand I have translated by “the Understanding”. Where the capital is omitted, the word has the usual English meaning.’ [39] Miller thus ‘tagged’ specifically technical terms with capitals, and his readers must trust Miller’s discretion here as a translator and a philosopher. However, although he translated several of Hegel’s works, Miller was not a professional philosopher. In early life he was profoundly influenced by Czech philosopher and adventurer František Sedlák, one of the co-founders of the utopian socialist Whiteway Colony near Stroud in Gloucestershire, where Miller sometimes lived. The translation of the Phenomenology began as a joint translation with American academic Peter Fuss. It seems that Miller and/or his publisher eventually rejected Fuss’s work, and Miller carried on alone, but with the support of J.N. Findlay, a renowned professor of philosophy who lent cultural capital to the project by writing an introduction and synopsis of the text. I am currently preparing a more detailed analysis and contextualization of Miller’s translation but can offer some initial findings here. Miller, like Baillie, uses a range of English terms for aufheben, but Miller’s first choice is supersede and supersession. For example, of the 55 occurrences of verbal and nominal forms of aufheben in the Consciousness chapter, Miller uses supersede/supersession 29 times, cancel 10 times, with 2 or 3 occurrences each of destroy, sublate and suspend. Miller’s choices seem to be determined by his sensitivity to the immediate linguistic context. For instance, in paragraph 156, he uses cancel where the direct object of aufheben is Unterschied (difference), presumably because Miller felt that a difference could not naturally or logically be superseded. [40]

While Miller modestly asserts his prowess as a translator by drawing attention in his foreword to Baillie’s ‘loose paraphrase’ and offering a guarded acknowledgement of the desirability of consistency, his tentative, in-text improvements fall short of the rigorous translational norms envisaged by Pinkard. In his major critical work on the Phenomenology, Pinkard lists Miller’s inconsistent translations of key Hegelian terms such as Ansichsein (being-in-itself), Wesen (essence) and Aufheben (sublation) and sums up that ‘[a]nybody trying therefore to pursue a close reading of the text only by relying on the English translation has a difficult task’. [41]

Circumspect germanizing

The high level of terminological consistency of Pinkard’s translations of every occurrence of Geist (spirit) and aufheben (sublate) makes it considerably easier for a modern reader to follow Hegel’s argument, especially with direct reference to the German source text which is printed alongside the translation in the 2008 online version. [42] As Pinkard claims in his translator’s notes, his approach allows the reader to take Hegel seriously as a philosopher, to appreciate the scientific rigour of Hegel’s language. However, in spite of this considerable achievement, Pinkard’s commitment to norms of terminological consistency and readability (which inevitably vie with one another at times) does not add up to a neutral or even transparent translation. The translation does not offer unmediated access to Hegel’s thought; it too is an interpretation as well as a rendering of the language. As with Baillie and Miller, aspects of Pinkard’s interpretation are embodied more or less explicitly in the language of the text. In fact, according to the radical contextualization offered here, the terminological consistency found in Pinkard’s translation should, itself, be regarded as an embodiment of his translatorial hexis. Although Pinkard explicitly seeks to secularize and depoliticize Hegel at one level, at another level Pinkard’s choice of terms and commitment to the norms of consistency and readability in the translation form components of a more subtle but nonetheless will-driven strategy for reappropriation and repoliticization of Hegel’s text specifically for use in the modern, neoliberal, largely anglophone academy.

Textual and paratextual features of the translation, such as the page layout, the glossary and translator’s notes, embody the translatorial hexis implicitly and explicitly, distinguishing it from its predecessors as a work embedded in the communicative dynamics of early-twenty-first-century academic publishing. For example, the two-column parallel-text arrangement implicitly re-Germanizes Hegel’s philosophy, drawing attention to the fact that this is a translation from German. [43] The publication of an online draft on the translator’s website since the copyright date of 2008 implicitly articulates Pinkard’s open, democratic stance. While the draft text is available free of charge for use in education, the published translation will be a costly product. [44] Pinkard refers explicitly to the provisional nature of the draft and to the ultimate involvement of the series editor from Cambridge University Press as co-translator. Pinkard’s explicit confession that there are ‘bound to be some errors’ also goes considerably beyond the traditional translator’s apology, portraying himself as human and humorous rather than aloof and unapproachable. The text is thus framed as potentially variable, not yet set in stone; readers are invited to participate in catching any blunders before it is too late. This apparently democratic hexis reflects Pinkard’s pedagogic habitus, his lecturing and teaching style. [45] The translator earns capital in the form of acceptance and ultimately honour in the eyes of the intended readership.

At one point in his translator’s notes, Pinkard switches to the first person singular: ‘I too have often been tempted…’; ‘I hope that in all instances I will have resisted that temptation.’ [46] These statements represent a declaration of Pinkard’s intention or ‘hope’ to abide by translational norms, [47] which he explains as follows:

I of course have my own interpretation of this book, but I hope that the current translation will make it easy for all the others who differ on such interpretive matters to be able to use this text to point out where they differ and why they differ without the translation itself making it unnecessarily more difficult for them to make their case. [48]

Pinkard’s position can be characterized as a hexis of circumspection which is congruent with Pinkard’s non-metaphysical, communitarian reading of Hegel’s recognition philosophy. As a translator, Pinkard takes his critical readers’ ability to ‘use this text to point out where they differ’ as a norm for his own translatorial agency. According to this self-imposed, complex norm, his success as a translator is dependent upon his (serious) critics being able to use the translation against Pinkard’s own view, in support of his critics’ different view. If Pinkard’s interpretation makes it more difficult for his critics to argue their opposing point of view, then the translation has, in some sense, failed. The particular sense in which the translation would fail under these circumstances relates to Pinkard’s reputation (hexis) in the academic sub-field of Hegelian studies. To have produced a translation biased in favour of one’s own interpretation, in full knowledge of the existence of many subtly conflicting interpretations of Hegel, would be dishonourable.

spirit with a small s

At the closest level of analysis, the translatorial hexis is discernible, for example, in the translator’s handling of the contested term Geist [mind/spirit/ Spirit]. By contrast with his predecessors, Pinkard consistently translates Geist as spirit with a small ‘s’. At this level of analysis, a microscopic, semantic tension is evident between Pinkard’s final choice and the other possible candidates, especially his predecessors’ choices. The focus here is on the (intensional) ‘sense’ of Pinkard’s use of the term rather than on the (extensional) ‘reference’ of Hegel’s term Geist itself. [49] The semantic tension is at least partially intertextual because Pinkard had to reject some of his predecessors’ choices (Spirit, mind, Mind) as well as some options (mind/spirit, Geist) used by other contemporary anglophone authors. [50] He lists his choice of spirit in the glossary but does not discuss his reasoning in detail. However, Pinkard frequently refers to Geist, spirit and, more recently, to mind and mindedness51 in his books and articles. The definition quoted below gives an indication of Pinkard’s particular sense of spirit in 1987:

I am using ‘spirit’ in what I take to be its basic Hegelian sense minus the metaphysical associations that Hegel gave it. I am not using it to denote any kind of metaphysical entity, as he did. For some, this might, of course, disqualify the usage as being ‘Hegelian’. Not much hangs on that, so I shall not belabour the point. [52]

In a more recent book, Pinkard gives another nonmetaphysical definition: ‘“Spirit” therefore denotes for Hegel not a metaphysical entity but a fundamental relation among persons that mediates their self-consciousness, a way in which people reflect on what they have come to take as authoritative for themselves.’ [53] The suggestion that spirit is not a metaphysical entity ‘for Hegel’ is controversial.

The non-metaphysical sense of spirit is presented as less than the full, metaphysical Hegelian reference. In the first quotation, Hegel’s precise referent is not the important issue: ‘Not much hangs on that’. Pinkard has subtracted the metaphysical dimension from Hegel’s Geist (‘minus the metaphysical associations’) in order to use the term spirit for his own non-metaphysical reconstruction. In the second quotation, this sense of spirit is presented as the core argument of Hegel’s philosophy.

Bearing in mind the Bourdieusian theorization of hexis elaborated in this article which is directly concerned with symbolic values, it is significant that spirit with a lower case ‘s’ is smaller than Spirit with an upper case ‘S’. The small ‘s’ of spirit as used in Pinkard’s translation symbolizes not only a circumscription of the scope of Hegel’s Geist but also a change in the stance or hexis of the philosopher/translator. Pinkard’s stance is deliberately less emphatic than that of Baillie, who controls the reception of Hegel’s terms, especially through lexical patterning and through his emphatic/explanatory use of capitals, and less subservient than Miller, who ‘tried’ to use capitals only ‘for terms which have a peculiarly Hegelian connotation’. Pinkard seeks respect not through rhetorical devices or extravagant metaphysical claims about Hegel’s ‘Spirit’ which are difficult to substantiate in a sceptical, scientifically orientated modern world, but rather by consciously and overtly circumscribing the extent of the claims made in order to render them more reasonable. Pinkard’s choice of spirit with a small ‘s’ embodies this important change of attitude in the text of the translation and thus assimilates this specific sense of spirit into the modern context. Pinkard’s spirit is comparable, for example, with President Obama’s reference in his inauguration address to the ‘spirit that must inhabit us all’ [54] and thus furnishes a way of understanding one sense of Hegel’s Geist without necessarily making (extravagant) claims about Hegel’s metaphysical referent. The translation thus reinforces some senses of Geist while deflecting the reader’s attention from others, such as the overlap between mind and spirit suggested by Baillie’s translation and the religious and/or metaphysical connotations of Spirit with a capital ‘S’.

It is also worth noting that Pinkard uses the term spirit many times more than Hegel uses the term Geist. Where Hegel uses a pronoun, such as it or which, Pinkard often replaces the pronoun with the noun (spirit) so that readers can more readily follow the cohesive chain of Hegel’s argument. The quotations at the end of this article provide a clear example of this strategy. The table opposite summarizes numerical findings. The total additional explanatory occurrences of spirit in the six main chapters of Pinkard’s translation amounted to around 200 tokens.

Pinkard’s aufheben: ‘forget about raising up’

Pinkard’s consistent translation of aufheben as sublate also contrasts intertextually with the Baillie and the Miller translations, [55] primarily in that it removes the apparent inconsistency of using several signs to translate a single referent; it also removes the rhetorical emphasis introduced by Baillie, especially in the later chapters of the book, by using two verbs (such as cancel and transcend or cancel and supersede); and it removes the spatial metaphors of height and transcendence connoted by Baillie’s and Miller’s selective use of transcend and supersede. These differences from the previous translations are not merely neutral improvements. As the next two examples show, Pinkard’s choice of the technical term sublate deflects readers of his translation from specific connotations of the German term and some of the rival English translations such as abolish and transcend while, at the same time, reinforcing the more circumscribed sense of sublate offered by Pinkard in the secondary literature.

First, both Helen Macfarlane’s original (1850) English translation[56] and Samuel Moore’s (1888) translation of the Manifesto of the Communist Party, [57] translate Engels’s use of the verb aufheben as abolish, most famously in the slogans ‘abolish private property’ and ‘abolish the family’. [58] While the ethically positive connotations of abolition with regard to the abolition of slavery may have appealed to Mac farlane and Moore, a more destructively revolutionary interpretation of the Hegelian/Marxian verb aufheben (sublate/abolish) may cause modern, liberal-minded interpreters, who seek to dissociate Hegel from Marxism, to steer clear of this English verb. Revolutionary connotations of the German term aufheben are still evident in online anglophone political discourse. Aufheben is the title of a British libertariancommunist magazine, the editors of which state:

There is no adequate English equivalent to the German word Aufheben. In German it can mean ‘to pick up’, ‘to raise’, ‘to keep’, ‘to preserve’, but also ‘to end’, ‘to abolish’, ‘to annul’. Hegel exploited this duality of meaning to describe the dialectical process whereby a higher form of thought or being supersedes a lower form, while at the same time ‘preserving’ its ‘moments of truth’. The proletariat’s revolutionary negation of capitalism, communism, is an instance of this dialectical movement of supersession, as is the theoretical expression of this movement in the method of critique developed by Marx. [59]

Pinkard’s choice of sublate deflects readers from this kind of politicised discourse, encouraging a less revolutionary interpretation of Hegel’s term than is signified by translations such as abolish, annul, do away with or even cancel, supersede or negate. While Pinkard is committed to taking Hegel’s terminology ‘seriously’, his sense of sublate could thus also be seen as embodying a de-politicising effect, especially in its semantic demarcation from some of the other candidate terms.

Second, Pinkard’s sense of sublate deflects from the spatial metaphor of height contained in the German term (the literal meaning of aufheben is lift up or raise up). Once again, reference to the wider context surrounding the translation and the translator illustrates this point. In YouTube video clips from his 2011 lecture tour in Romania, Pinkard refers to the ambiguity of the term aufheben. He explains that three meanings of aufheben (cancel/preserve/ lift up) are conventionally suggested in the literature on Hegel. [60] The third of these meanings, raise up, Pinkard continues, has been used to support the idea (associated with Marx’s reading of Hegel) that Hegel’s philosophy is concerned with a kind of totalizing idealism according to which there is a historical progression through ever ‘higher’ levels towards the totality of Absolute Spirit. Pinkard suggests the danger of this view and stresses that Hegel never refers to the third of these meanings: ‘aufheben has only two meanings, negate and preserve. Forget about raising up.’ The following transcription from the video clip illustrates Pinkard’s positive understanding of aufheben as a ‘wonderful metaphor’ concerned not with rising to ever higher levels of metaphysical totality but rather, for example, with the kind of circumscription of property rights associated with democratic-liberal, communitarian politics:

Instead of thinking of this process [aufheben] as going upwards, think of it as going from side to side, horizontal rather than vertical – that’s a metaphor – but nonetheless to aufheben something is to circumscribe its authority. Something is aufgehoben (sublated) in Hegel when the authority it has over you or it has over someone else is cancelled, circumscribed, limited by moving to a new context where you are not exactly denying the old claim but you’re now limiting it in a certain way so that you are both cancelling it and preserving it. So, for example, Hegel says I have a right to private property. This is changed in morality; it’s not that I lose all my property but, no, it turns out that I can’t do anything I want with it, particularly if it means the violent harming of another person. In fact it’s a wonderful metaphor. [61]

Although Pinkard does not wish to force his sense of sublate onto readers of the translation (or indeed attendees at his lecture), he does seek to keep open the possibility of this positive, politically and socially promising, democratic-liberal concept of circumscription, which he associates with aufheben, by deflecting attention away from the potentially dangerous spatial metaphor of height and lifting or raising up with its ethically negative connotations, for example, of elitism, ethnocentrism and totalitarianism. Pinkard’s bodily gestures of lateral rather than vertical extension, and of circular enclosure and protection or preservation, shown in the video clip therefore also embody the translatorial hexis.

Extremely mindful approximations

In conclusion, the following passage taken from the last paragraph of Hegel’s text and the three translations discussed here contains the last occurrence of the term Aufheben in the Phenomenology and exemplify similarities and differences between the translators and their work:

Das Geisterreich, das auf diese Weise sich in dem Dasein gebildet, macht eine Aufeinanderfolge aus, worin einer den anderen ablöste und jeder das Reich der Welt von dem vorhergehenden übernahm. Ihr Ziel ist die Offenbarung der Tiefe, und diese ist der absolute Begriff; diese Offenbarung ist hiermit das Aufheben seiner Tiefe. [62]

BAILLIE: The realm of spirits developed in this way, and assuming definite shape in existence, constitutes a succession, where one detaches and sets loose the other, and each takes over from its predecessor the empire of the spiritual world. The goal of the process is the revelation of the depth of spiritual life and this is the Absolute Notion. This revelation consequently means superseding its ‘depth’. [63]

MILLER: The realm of Spirits which is formed in this way in the outer world constitutes a succession in Time in which one Spirit relieved another of its charge and each took over the empire of the world from its predecessor. Their goal is the revelation of the depth of Spirit, and this is the absolute Notion. This revelation is, therefore, the raising-up of its depth. [64]

PINKARD: The realm of spirits, having formed itself in this way within existence, constitutes a sequence in which one spirit replaced the other, and each succeeding spirit took over from the previous spirit the realm of that spirit’s world. The goal of the movement is the revelation of depth itself, and this is the absolute concept. This revelation is thereby the sublation of its depth.[65]

It is important to understand that there is very little intrinsically wrong in any of the translations. They are all extremely mindful approximations. It is evident from the comparison that the translators are trying to articulate complex ideas as clearly as they can. The focus of interest in comparing the quotations is not to judge one as better than the other but rather to understand how and why they differ. In his translation of the passage cited, Baillie added the phrases: ‘and assuming definite shape’; ‘spiritual’ in ‘empire of the spiritual world’; ‘of the process’; and ‘of spiritual life’. He translated ‘Reich’ as ‘realm’ and ‘empire’, capitalized ‘Absolute Spirit’, and placed quotation marks around ‘depth’. This approach to the translation presumably exemplifies what Miller criticized as ‘loose paraphrase’. However, Miller also added the phrases ‘in Time’, ‘of its charge’ and ‘of Spirit’. By contrast with his general preference for supersede and supersession, which was used by Baillie, Miller translated aufheben here as ‘the raising up’. Pinkard, in turn, added ‘spirit’ four times, the phrase ‘of the movement’ and ‘itself’ after ‘revelation of depth’. I believe the preceding discussion of translatorial hexis assists our understanding of the differences and similarities in the translations, drawing attention, for example, to what was at stake for the translators in their different translations of Geist and aufheben. According to this radical contextualization, Pinkard’s translation itself argues, against its predecessors, that Geist need not necessarily be understood as an extravagant metaphysical or religious entity, and aufheben need not necessarily imply a hierarchical transcendence or supersession. To bracket out the translatorial hexis or to dismiss it as an irrelevant ad hominem distraction from the universal principles sought in Hegel’s philosophy runs the risk of losing an illuminating dimension in our reading of translated philosophy and reveals ultimately unsustainable presuppositions about the nature of language and translation.

Notes

1. ^ Recent developments in translation and interpreting studies are summarized in Mona Baker, ‘The Changing Landscape of Translation and Interpreting Studies’, in A Companion to Translation Studies, ed. Sandra Berman and Catherine Porter, Wiley-Blackwell, New York, 2014, pp. 15–27.

2. ^ The case of Hegel’s Phenomenology in anglophone translation is topical for a number of reasons discussed in this article. A general growth of interest in Hegel’s philosophy has been noted in, for example, Stephen Houlgate, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, Bloomsbury Academic, London and New York, 2013, pp. 191–4. The three translations considered in my article – Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, G.W.F. Hegel: The Phenomenology of Mind, trans. James Black Bail ie, Dover Publications, New York, 2003 (based on the 1931 edition); Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.J. Miller, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1977; Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. Terry Pinkard, published online at terrypinkard.weebly.com, copyright 2008 – awaiting publication by Cambridge University Press – are all readily accessible. (This article refers only to the original, online draft version of Pinkard’s new translation.) Another new translation by Nicholas Walker was announced in Kenneth Westphal, The Blackwell Guide to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, Blackwell, Oxford, 2009, p. 297. A further translation, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Hegel and his Philosophy: Mind/Spirit, trans. David Healan, Geocities, Midpoint, Berlin and Yokohama, 2007, was published online to mark the 200th anniversary of the first publication of Hegel’s book in 1807. It should also be noted that a Kindle e-book version of the 1931 edition of Bail ie translation is also available. It cannot therefore be assumed that students will always consult the same text. A practical response to this bewildering diversity of translations is suggested in the conclusion.

3. ^ The concept of translatorial hexis is presented in David Charlston, Hegel’s Phenomenology in Translation: A Comparative Analysis of Translatorial Hexis, PhD thesis, CTIS, University of Manchester, 2012; and in David Charlston, ‘Textual Embodiments of Translatorial hexis in the J.B. Bail ie Translation of Hegel’s Phenomenology’, The Translator, vol. 19, no. 1, 2013, pp. 51–80.

4. ^ For example in Wil ard Quine, Word and Object, Technology Press of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge MA, 1960; Walter Benjamin, ‘The Task of the Translator’ (1968), in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, Harcourt Brace, New York, 1996; Jacques Derrida, Glas, Galilée, Paris, 1974.

5. ^ Anthony Pym, ‘Philosophy and Translation’, in Piotr Kuhiwczak and Karin Littau, eds, A Companion to Translation Studies, Multilingual Matters, Toronto, 2007; Rosemary Arrojo, ‘Philosophy and Translation’, in Yves Gambier and Luc Van Doorslaer, eds, Handbook of Translation, John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 2010; Kirsten Malmkjaer, ‘Language, Philosophy and Translation’, in Yves Gambier and Luc Van Doorslaer, eds, Handbook of Translation, John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 2012.

6. ^ Referenced, for example, in Lisa Foran, ed., Translation and Philosophy, Intercultural Studies and Foreign Language Learning, Peter Lang, Bern, 2012; Kathryn Batchelor, ‘Translation and Philosophy’, International Journal of Philosophical Studies, vol. 23, no. 1, 2013, pp. 122–6.

7. ^ Terry Pinkard, Hegel’s Phenomenology: The Sociality of Reason, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994, pp. 17–18; Stephen Houlgate, The Opening of Hegel’s Logic, Purdue University, West Lafayette IN, 2006; Kenneth Westphal, The Blackwell Guide to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, Blackwell, Oxford, 2009, p. ix.

8. ^ Ian Mason, ‘Discourse, Ideology and Translation’, in Mona Baker, ed., Critical Readings in Translation Studies, Routledge, Oxford and New York, 2010, pp. 83–95.

9. ^ Daniel Simeoni, ‘The Pivotal Status of the Translator’s Habitus’, Target, vol. 10, no. 1, 1998, pp. 1–39.

10. ^ Terry Pinkard, ‘What is the Non-Metaphysical Reading of Hegel? A Reply to Frederick Beiser’, Bul etin of the Hegel Society of Great Britain 34, 1996, pp. 13–20.

11. ^ Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1977. For sociological approaches to translation studies, see for example the special issue of The Translator, vol. 11, no. 2, ed. Moira Inghil eri, 2005.

12. ^ Randal Johnson, ‘Editor’s Introduction: Pierre Bourdieu on Art, Literature and Culture’, in Pierre Bourdieu: The Field of Cultural Production, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1993, p. 9.

13. ^ Theo Hermans, ‘The Translator’s Voice in Translated Narrative’, Target 8, 1996, pp. 23–48; Michael Cronin, Translation and Globalization, Routledge, London and New York, 2003 (for the idea of translatorial presence); Dimitris Asimakoulas, ‘Systems and Boundaries of Agency: Translation as a Site of Opposition’, in Dimitris Asimakoulas and Margaret Rogers, eds, Translation and Opposition, Multilingual Matters, Bristol, 2011 (for the idea of translatorial agency); Lawrence Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation, Routledge, Oxford, 2010.

14. ^ Pierre Bourdieu, Homo Academicus, trans. Peter Collier, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1988; Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, trans. Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1991; Pierre Bourdieu, The Political Ontology of Martin Heidegger, trans. Peter Collier, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1991.

15. ^ Simeoni, ‘The Pivotal Status of the Translator’s Habitus’, p. 5.

16. ^ ‘Bodily hexis is political mythology realised, em-bodied, turned into a permanent disposition, a durable manner of standing, speaking, and thereby of feeling and thinking. The oppositions which mythico-ritual logic makes between the male and female and which organise the whole system of values reappear, for example, in the gestures and movements of the body, in the form of the opposition between the straight and the bent, or between assurance and restraint.’ Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, 1977, pp 93–4.

17. ^ According to Gérard Genette (Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997), paratexts are the texts added to the principal text by authors, editors or translators, such as the introduction, footnotes and index.

18. ^ Jon Stewart, The Hegel Myths and Legends, Northwestern University Press, Evanston IL, 1996; Peter Singer, Hegel: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001; Stephen Houlgate, An Introduction to Hegel: Freedom, Truth and History, Blackwell, Oxford, 2005.

19. ^ Terry Pinkard, Democractic Liberalism and Social Union, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1987. For a full discussion of Marx’s ‘misunderstanding’, see Houlgate, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, pp. 96–7.

20. ^ See Daniel Bell, ‘Communitarianism’, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward Zalta, Stanford University, Stanford CA, 2012; John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1971.

21. ^ Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia, Basic Books, New York, 1975.

22. ^ Pinkard, Democratic-Liberalism and Social Union; Pinkard, Hegel’s Phenomenology: The Sociality of Reason.

23. ^ See Pinkard, Hegel’s Phenomenology: The Sociality of Reason, p. 3.

24. ^ See, for example, Frederick Beiser, The Cambridge Companion to Hegel and Nineteenth Century Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2008, pp. 1–42; James Kreines, ‘Hegel’s Metaphysics’, Philosophy Compass, vol. 1, no. 5, 2006, pp. 466–80; Paul Redding, ‘Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward Zalta, Stanford CA, 2010; Robert Stern, Hegelian Metaphysics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009, pp. 1–41.

25. ^ Frederick Beiser, ‘Hegel, A Non-Metaphysician? A Polemic’, Bul etin of the Hegel Society of Great Britain 32, 1995, pp. 1–13; Tristram Engelhardt and Terry Pinkard, eds, Hegel Reconsidered: Beyond Metaphysics and the Authoritarian State, Springer, Heidelberg, 1994; Frederick Beiser, ‘Response to Pinkard’, Bul etin of the Hegel Society of Great Britain 34, 1996, pp. 21–6.

26. ^ Beiser, ‘Hegel, A Non-Metaphysician? A Polemic’, p. 12. 27. Pinkard, ‘What is the Non-Metaphysical Reading of Hegel?, p. 13.

28. ^ Ibid, p. 20. 29. See Kimberly Hutchings, Hegel and Feminist Philosophy, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2003. Hutchings sees a potential within Hegel’s philosophy for a ‘feminist’ interpretation which could provide a valuable compromise between ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘communitarian’ approaches to social and international relations. Hegel himself did not see this potential.

30. ^ Terry Pinkard, ‘What is the Non-Metaphysical Reading of Hegel?, p. 15.

31. ^ Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Phänomenologie des Geistes, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, 1970.

32. ^ This view is explained, for example, in Houlgate, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit.

33. ^ Terry Pinkard, Hegel: A Biography, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

34. ^ David Charlston, ‘Translating Hegel’s Ambiguity: A Culture of Humor and Witz’, in Lisa Foran, ed., Translation and Philosophy, Peter Lang, Bern, 2012, pp. 27–39.

35. ^ The Phenomenology of Mind, trans. Bail ie, p. xi.

36. ^ Charlston, Hegel’s Phenomenology in Translation, p. 131; ‘Textual Embodiments’, p. [64] .

37. ^ The Phenomenology of Mind, trans. Bail ie, p. 250. 38. Charlston, ‘Textual Embodiments’, p. [68] .

39. ^ Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. Miller, p. xxxi.

40. ^ Hegel, Phänomenologie des Geistes, ‘daẞ die Unterschiede nur solche sind, die in Wahrheit keine sind und sich aufheben’ (p. 127); Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. Miller, ‘that the differences are only such as are in reality no differences and which cancel themselves’ (p. 96).

41. ^ Pinkard, Hegel’s Phenomenology: The Sociality of Reason, p. 17.

42. ^ I verified the consistency of Pinkard’s translations of every occurrence of Geist (spirit) and aufheben (sublate) in detail using WordSmith 5.0 concordancing software. Details of the analysis are given in Charlston, ‘Hegel’s Phenomenology in Translation’, pp. 133–93.

43. ^ Many of the footnotes act in the same manner, glossing problematic terms in German, and possibly inviting comment from German-speaking peers. The Miller translation, by contrast, is discreetly de-Germanized.

44. ^ Pinkard also kindly gave permission for me to convert the pdf version of his online draft into text format in order to carry out the concordance analyses presented in my PhD thesis (Charlston, ‘Hegel’s Phenomenology in Translation’).

45. ^ This suggestion is supported by students’ generally positive comments on Pinkard as a professor on the Rate My Professor website: www.ratemyprofessor.com. [archive]

46. ^ Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. Pinkard, p. i.

47. ^ A discussion of translational norms and especial y ‘complex norms’ is provided in Andrew Chesterman, ‘From “Is” to “Ought”: Laws, Norms and Strategies in Translation Studies’, Target, vol. 5, no. 1, 1993; Mona Baker, ‘Norms’, in Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, ed. Mona Baker and Gabriele Saldanha, Routledge, London, 2011, pp. 189–93.

48. ^ Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. Pinkard, p. i.

49. ^ A discussion of Frege’s distinction in the context of translation studies is provided in Malmkjaer, ‘Language, Philosophy and Translation’. The reference for the Frege essay is: Gottlob Frege, ‘Über Sinn und Bedeutung’, Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik 100, 1892, pp. 25–50; ‘On Sense and Reference’, ed. and trans. Peter Geach and Max Black, in Translations from the Philosophical Writings of Gottlob Frege, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1977.

50. ^ For example, David Healan in Hegel and his Philosophy uses mind/spirit to translate Geist. Many anglophone writers refer directly to the German term Geist. Pinkard’s choice of spirit thus de-problematizes the term by comparison with these options.

51. ^ Terry Pinkard, Hegel’s Naturalism: Mind, Nature, and the Final Ends of Life, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012.

52. ^ Pinkard, Democratic-Liberalism and Social Union, p. 188. 53. Pinkard, Hegel’s Phenomenology: The Sociality of Reason, p. 9.

54. ^ Barack Obama, ‘Inaugural Address’, New York Times, 20 January 2009.

55. ^ Pinkard refers explicitly to Miller’s translation in his own translator’s notes and in Hegel’s Phenomenology: The Sociality of Reason, pp. 17–19. He also refers to earlier writers on Hegel who have tended to obscure the meaning of aufheben.

56. ^ David Black, Helen Macfarlane, Lexington Books, New York, Toronto and Oxford, 2004, pp. 137–70.

57. ^ Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party, in Karl Marx: Selected Writings, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1977, p. 15.

58. ^ This point is also mentioned in Ralph Palm, ‘Hegel’s Concept of Sublation’, PhD thesis, Institute of Philosophy, Leuven, 2009; but without reference to libcom.org.

59. ^ libcom.org, ‘Aufheben’, www.libcom.org/aufheben/about [archive]; accessed 5 April 2012.

60. ^ Pinkard is possibly thinking of Michael Inwood, A Hegel Dictionary, Blackwell, Oxford, 1992.

61. ^ Terry Pinkard, ‘From Hegel to Marx: What Went Wrong?’, 2011, www/youtube.com/watch?v=9y204W08dzk [archive]; accessed 26 January 2013, The quotation occurs in video clip 3, approximately 17 minutes from the start of the clip.

62. ^ Hegel, Phänomenologie des Geistes, p. 591. 63. The Phenomenology of Mind, trans. Baillie, p. 476.

64. ^ Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. Miller, pp. 492–3.

65. ^ Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. Pinkard, p. 735.