We’re used to one-way neoliberalism, regardless of party, in which we keep getting more of its familiar features: public budget austerity, marketisation, privatisation, selective cross-subsidies favouring business and technology, precarisation of professional labour, and structural racism. But under the pressure of international social forces, neoliberalism is increasingly breaking down. These forces include the Covid-19-induced public health crisis, the climate emergency, multiple modes of racism and neo-colonialism, and the grinding effects of economic inequality. Neoliberalism has fractured in places like Hungary and Turkey, where it is being replaced by an authoritarian form of national capitalism. 1 Something like that was happening in the US under Donald Trump, who sponsored a new round of tax cuts while denouncing trade liberalisation. At the same time, the liberal centre, incarnated by ‘third way’ New Democrat Joe Biden, has been backing away from the tradition that runs from Reagan and Thatcher through Clinton, Obama and Blair.

Biden’s American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan are less interesting for content or size than as symbolic actions. They mark a clear paradigm shift away from a forty-year ruling consensus about rightful business sovereignty over the economy. 2 The AJP’s 12,000-word ‘Fact sheet’ declares four decades of conservative economics a failure for national life. It casts Reaganomics as a mode of underdevelopment applied to the country’s own working people and to its populations of colour, which resulted in a weakened society unable to rely on its decrepit public systems when it most needed them, as during the Covid-19 pandemic, and in the context of new great power rivalries. On the important level of paradigm framing, Biden’s AJP aims not only to avoid the mistakes of Obama, Geithner and Summers but also of Roosevelt, Kennedy and Johnson: it is not colour blind but race conscious, and promises to distribute resources in a way that explicitly redresses racial disparities. For example, of the $40 billion that Biden requests for upgraded research infrastructure, half is to go to Historically Black Colleges and Universities and other Minority Serving Institutions. The US Senate will wreck this plan, of course. But the framework is out there: the owl of Minerva has flown in daylight.

The public critiques of austerity we’ve seen from Biden and also Boris Johnson won’t go very far on their own. But in multiple domains – energy, policing, housing, banking and finance – the recent phase of ‘punitive’ neoliberalism is losing its political base. 3 A series of big reformist packages in the US, and bailouts for almost everything except universities and the arts in the UK, are opportunities for the higher education world to supplement its still-very-necessary critiques of the neoliberal, the racist and the settler-colonial university with plans for radical reconstruction.

At least four futures

My first point here is that the current situation puts higher learning up against a conflicted neoliberalism that is being forced to cede ground to opposing tendencies on both left and right, and my second is that multiple paths are now possible for the Anglo-American university in the 2020s. My third is that which paths universities follow depends not just on government policy but on the goals and actions of social movements outside but also inside of universities. I’ll take these in order.

Universities are heading not only towards a familiar future but also toward three other futures that various

people have been imagining. These are really four modes of future study. They aren’t just abstract possibilities. The idea is that each can be generated by ratios of developments along the axes indicated there.

The first future might be called Fragmented Decline – made from the combination of privatisation (x axis) and platform (y-axis), replacing democratic deliberation with corporate managerialism. This is the business as usual track: the joyless storyline of ‘decline foretold’. The conditions of this future were present before but were locked into place by policy and weak administrative responses in the 2010s, a decade that saw considerable increases in both privatisation in and managerial control of British universities. In the UK, David Willetts and the Coalition government cut central funding and replaced it with fees supported by student loans, producing an explosion of student debt. At the same time, managerial audit and direct control of teaching and research also increased, signalled by a proliferation of indicators, particularly the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) and the Longitudinal Educational Outcomes (LEO).

These indicators are regarded by professionals as deeply flawed – as measures of teaching quality or learning quantities. As techniques of induced compliance, on the other hand, they have been highly successful. As a measure, the LEO simply correlates an alumni’s present income stream with their past course. It has no basis for making claims that participation in the course generated the income; more fundamentally, income is an effect of the way the job market prices vocations, not university instruction, so it is simply measuring something other than what is in its name. And yet, like the TEF, it has extended rankability and stratification among universities, forced the new ‘losers’ to scramble to increase the kinds of functions and behaviours for which the indicators select, and enhanced the authority of government to tell the sector what to do. 4 The main results have been fragmentation of the sector’s purposes, increased resource inequality, greater poverty for the institutions most likely to educate the country’s poorer students and students of colour, and decline in net educational resources for most if not all universities. Fragmented decline is a future we already know.

A second possible future is Debt-Free College. Although reformist, this future would require a major break with forty years of higher education policy. Here the Sanders-Warren tendency builds on Biden’s opening to develop ‘College for All’ into a New Deal for Higher Education (to name a pair of US projects within this tendency). Labour’s Corbyn-era National Education Service sketched a UK version, though after Corbyn any future version of this idea will likely need to be pushed by civil society groups. In this future, some kind of new New Deal would generate debt-free university for all students. This can only happen, as a practical matter, through tuition-free higher education. 5 The tax system would need a major adjustment to make this work, which would in turn require continuing high levels of popular organisation and escalating political pressure. However, free college, while keeping student costs low, would retain the current inequality of university resources – an inequality that is profoundly racialised. In this second future, college would become cheaper but also remain as unjust as it is today. Since lower tuition would, without major state intervention to compensate for it, also lower each university’s revenues, the Debt-Free future for students might mean more institutional debt and insecurity for universities. That, in turn, would mean more educational inequality and mediocrity.

A third possible future is Funding Equalised. Here, various social movements might use the Biden opening to push College for All towards the overcoming of structural racism and class inequalities in educational resources. This would involve an entirely new political economy for higher education. It would distribute resources to achieve equality of economic inputs across different student populations, and invert those inputs according to need: less prepared students would get more instructional resources, not fewer as in the current state of affairs. The explicit goal here is equality of educational outcomes. It would use the tax system to redress injustices of income distribution, injustices that reflect the historical interaction of settler-colonial / imperial and neoliberal forms of accumulation. It would define educational needs and budget them accordingly, rather than today’s reverse practice of establishing budget scarcity and then allotting educational opportunities accordingly.

A fourth possible future is abolitionist, and aims to dismantle the current university altogether, in order to replace it with fully non-capitalist and decolonised processes of higher learning. Ideas about how this system might work could be taken from existing Indigenous educational structures and epistemes, and would develop over the process of their construction. These processes would be inspired by varying combinations of Indigenous, decolonial and anti-racist thought, including their critiques of the epistemologies of the global North.

This fourth and most ambitious future rests on criticism of public-good theories of the social effects of higher education, as, among other things, being grounded in the land-grant and ‘land grab’ of settler-colonial appropriation. 6 The critique of neoliberalism has confirmed abolitionist insights into various abuses of the commons. In his new book In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower, for instance, Devarian Baldwin shows how public colleges have used their non-profit status to support private developer control of the city. 7 Given its concern about public funding as a crossroads of colonial and expropriative forces, this fourth future is unlikely to make claims on the resources of national or state tax systems. It may consist of local initiatives that reflect situated epistemologies and entangled identities. These might privilege self-organisation in quasi-permanent autonomous zones. These activities are likely to take place in civil society and would be private in that sense, although collectively and communally organised. They would have many models to draw on for organisation, including cooperatives, freedom schools, tribal colleges, related social systems and social movement services.

Much valuable work has been done to demarcate abolitionist from anti-neoliberal / anti-racist and public good transformations. 8 The lineages are distinct, as indicated in the four-quadrant graphic. The histories of Indigenous people, foregrounded in abolitionist futures, have developed in violent conflict with the public land-grant universities that grew out of settler-colonial expansion. Those memories and those differences must be respected and preserved. Neoliberal and neo-colonial logics also interacted in the past, and continue to interact. For example, techniques of privatisation deprive the descendants of British colonial subjects of the teaching grants and maintenance grants that were available to the overwhelmingly white student populations of the 1990s and 2000s expansion: both anti-neoliberal and decolonial critiques are relevant here. I’ll discuss below a similar pattern in the University of California.

Elements of Futures three and four are likely to develop together. I put abolition on the private end of the private-public axis because it is grounded in part on a refusal of settler-descended public-good frameworks, and is likely to work with local contexts, differences and resources, at least in the beginning. However, I would like to see its autonomous institutions funded by the wider society through the tax mechanism, and increased in scope without reduction of independence or distinctiveness of values, epistemes and practices. I think we must do both. The same is true for the relations among other possible futures. Debt-free seems like a half-way measure, and it is, but would still require a massive upheaval in the political economy and group psychology of both the US and the UK to bring it about. The immense energy required to achieve it could itself lead to further things.

Critical university studies

The effects of the combination of managerialism and privatisation on students, instructors, researchers and frontline staff started to become clear to me in my workplace, the University of California, around the turn of the century, and by 2003 or so I set to work more systematically on their causes and effects. One goal was to figure out the effects of these shifts. The student debt boom was one, but there were less visible ones like the moving of research funding out of the humanities. Another was to identify the mechanisms that created these effects so that academics, including operations staff and students, could address them more effectively. We had to seek something like the truth behind the nonstop marketing that universities directed at politicians, executives, students and parents. For example, the marketing said that low-income students had a free ride at university, while the data showed they borrowed as much money as middle-income students: the latter needed to be demonstrated and then broadcast. 9 We needed to explain the mechanisms: how exactly did the ‘high tuition – high aid’ US model increase student debt? I saw the work as a materialist investigation of the university’s political economy, building on previous landmarks like Slaughter and Leslie’s Academic Capitalism (1997), working from the humanities rather than the social sciences or the science and technology business end of the university, and unearthing technical processes as well as undesirable educational and social effects. As the public university’s non-recovery from the financial crisis got underway in the 2010s, I hoped this mixed study of culture, institutions and finance would increase workplace activism among my academic colleagues, including students. My aim was to transform existing universities rather than exit from or abolish them, though current practice is so entrenched and so discursively powerful that straight abolition may ultimately prove more feasible. I will return to this point.

In 2012, Jeffrey Williams dubbed the interdiscipline of this kind of work ‘critical university studies’ (CUS), writing,

A dominant tenor of postmodern theory was to look reflexively at the way knowledge is constructed; this new vein looks reflexively at ‘the knowledge factory’ itself (as the sociologist Stanley Aronowitz has called it), examining the university as both a discursive and a material phenomenon, one that extends through many facets of contemporary life. … CUS turns a cold eye on higher education, typically considered a neutral institution for the public good, and foregrounds its politics, particularly how it is a site of struggle between private commercial interests and more public ones. … [It] analyses how higher education is an instrument of its social structure, reinforcing class discrimination rather than alleviating it.

I’d insist too on the university’s reinforcing racial discrimination, since the defunding of relatively accessible universities coincided with the increase of people of colour in the student population: the 1980s culture wars on anti-racist interventions were soon intertwined with budget wars that reduced the financial autonomy of public universities. 10

CUS knowledge had to be activist knowledge since internal disruption is the only thing that will keep the default future of fragmented decline from continuing indefinitely. This is because the privatised-managerial model delivers an economically functional outcome. It’s not the outcome that universities market, but it fits well with contemporary capitalism. Furthermore, no one explains to the public how the real and the marketed outcomes differ. This explanation became another CUS goal.

CUS sought to explain how the present model actually worked and show that its cures deepened the disease: tuition hikes, student debt, debt-funded capital projects, corporate research sponsorships were mostly net negative on revenues, with the major exception of student tuition, or required price-gouging of the university’s own community, as with public-private partnerships for student housing. 11 The present model generates the first future as its default outcome. The high-tuition / financial aid model then continues as it is. Student debt rises, though more slowly. Institutional debt rises. Public funding remains stagnant and ripe for cuts at the first whiff of a fiscal downturn. The financial conditions of different types of universities continue to diverge. The more selective institutions with the largest private endowments are insulated from fiscal crisis, while all others struggle, compromise, often decline and sometimes close.

It’s possible to assume that this is just how neoliberal capitalism works, so universities are inevitably mirroring larger economic forces. This implies that making universities less damaging must first wait for wider social change, or even a true revolution. 12 I understand the appeal of this view, and yet it underplays intermediating steps, internal variation and the partial or relative autonomy of all sectors in the economy. Universities have multiple simultaneous identities and contradictory effects. They are settler-colonial institutions in the US, and imperial or post-colonial institutions in the UK, that governments expect to deliver the technology for permanent military and economic supremacy on the world stage; at the same time, they sponsor autonomous research that is often anti-statist, anti-capitalist, anti-racist and anti-imperialist.

Just as fundamentally, they sponsor basic research pursued by people who are not primarily motivated by financial gain, meaning that, imperfect as their methods may be and biased as they individually are, the process and results are relatively independent of the economy and the state. Universities are widely regarded on the political right in both countries as a systemic menace to political and social order, and indeed sometimes they are. As I write, the Johnson administration is expanding a campaign to demonise critical race theory and to purge members of cultural boards perceived to be insufficiently anti-woke; it signals the seriousness with which conservatives regard university ideas in their everyday operations. The US culture wars were revived by Trump and are being amped up again as a weapon against Biden’s movement towards economic and social inclusion: these crusades are too well known to need further explanation.

Reproducing inequalities

My corner of CUS has focused in particular on the intermediary steps through which the university generates a stratified graduate population that increases the concentration of accumulated wealth. The easiest way to show this is in the form of a devolutionary cycle, in which each apparently discrete effect, like student debt, is enabled and intensified by the one that came before. 13

In brief, by the 1990s, senior university managers generally accepted the dominance of the view that higher education was like any other product marketed in a competitive economy: it would be most efficiently produced and delivered by private-sector methods, and should be treated, and paid for, as a private good. Even if they personally disagreed, and knew that even standard economics granted non-monetary and social benefits to higher education, they felt they had to get with the programme or suffer political ostracisation and fiscal decline. They committed themselves to pursuing private revenue streams – philanthropy, corporate contracts, real estate and other partnerships – as well as government contracts, whose net operating revenue results are negative (working through these accounts is an arena of technical labour that CUS often entails). The only good net positive private revenue source is student fees – in spite of the endless pitching of alternative revenue streams. This is a key point that needs to be taken on board by both critics and policymakers: the only reliable net positive private revenue is student tuition. This explains the fact that in the 2000s US public universities increased tuition charges at a multiple of the rate of inflation, or the fact that UK universities instantly tripled fees after the Cameron-Willetts Coalition government policy changes in 2011.

Next, the presence of student fee revenue encourages governments to cut tax-based state funding: Cameron-Willetts typically accompanied their increase in the fee cap with massive cuts in the teaching grant. This increases universities’ resource dependency on students’ private financial capacities. They offer students various loan mechanisms so they can pay tuition with money they don’t actually have. Universities also pursue overseas students (and, in the US, students from other states) who pay double or triple the rate of ‘home’ fees. Public universities also create high-fee for-profit masters’ programs for the same reason. The general outcome is that student debt becomes a personal hardship for many or most graduates, turns a bachelor’s degree from career springboard to financial burden, and damages the university’s standing with the general public, who increasingly see it as just another costly business to be watched out of the corner of their eye. Political blowback from debt, and the disappearance of the readily-available post-university job, induces continuous university cost-cutting in an atmosphere of political hostility. Managers often move money from the educational core to prospectively profitable auxiliaries, which reduces educational quality. The struggles of non-wealthy institutions lowers the degree attainment of their students and increases inequality across higher education.

This all leads to a graduate population whose unequal educational experiences generate unequal economic benefits (to say nothing of non-economic benefits). The advertised result of a B.A. degree is entrance to a good, fulfilling job and a stable financial future – in the US, it was the ‘American dream’ of a middle class life, supposedly still offered to a multi-racial student population. 14 The actual result of a B.A. degree is the limiting of this kind of affluence to a smaller elite – without expressly denying B.A. access to everyone else. We can refer to this as the US public university decline cycle.

Our default first future is one in which the current neoliberal political economy, using privatisation and managerial structures, creates a highly functional segmentation within the population of university graduates. In this system, wealthy super-premium private universities continue to do extremely well with global brands resting on endowment wealth that has benefitted from 40 years of financial asset price inflation, itself the result of systematic, bipartisan government policy. In the United States there are around 16 of these institutions. In the UK, there’s Oxford, Cambridge, UCL, LSE, Imperial, and you could perhaps include Kings College London and Manchester among others, but probably not the entire Russell Group. In the US, you could throw in the ‘Annapolis group’ of liberal arts colleges (many not wealthy) and you have seats for 3-5% of college students. Another group of US universities that are selective to some degree, maybe 400 in total, tread water in this future, and keep their heads above it depending on regional and other factors. Mostly they can attract and retain students only by continually reducing their own net operating revenues. The third group of ‘open access’ colleges includes everyone else. In the US, they number about 3800. These will be funded as job training centres, or left to struggle, consolidate or close. The UK version is the sudden Tory re-discovery of further education, to be put in budgetary competition with higher education.

These three groups of colleges produce very different typical levels of learning (in spite of the heroic efforts of their instructors and students). Group I offers customised programmes with lots of individual feedback. Group III is, in the US, run on nearly 100% adjunct instruction and offers working conditions too poor to do anything but provide generic and increasingly automated feedback. As David Laurence discovered, in ‘[m]ore than 50%, or 2,188 institutions, deep in the universe of United States degree-granting colleges and universities, one has yet to encounter a single tenured or tenure-track faculty member.’ 15

Occupying the great middle ground of relatively selective institutions, Group II is closer to Group III than one might think. For example, at UC Santa Barbara (30% acceptance rate), in the department where I taught for three decades, perhaps 5% of English majors write a senior thesis. Thus only a small minority of a generally very bright population of UCSB English graduates are likely to be competitive in their academic skills with students from places like Princeton University or Reed College, where senior theses are required. To summarise roughly, gross resource inequality leads to inequality of student learning. In this status-quo future, Fragmented Decline, we have premium learning at the top, and limited learning in various gradations for everyone else – especially for a group I haven’t even mentioned, the 50% of US college starters who leave without a degree.

The political economy of higher education is a clear example of racial capitalism in action. In a landmark study, ‘Separate and Unequal‘ (2013), Anthony Carnevale and Jeff Stohl found that after 1995, most newly enrolled Black and Latinx students attended open-access institutions while their white contemporaries mostly went to selective colleges, which have much higher graduation rates. Crucially, the study correlated the racialised variation in graduation rates with large differences in (instructional) expenditures per student: ‘The 82 most selective colleges spend almost five times as much and the most selective 468 colleges spend twice as much on instruction per student as the [3800-odd] open-access schools.’ 16

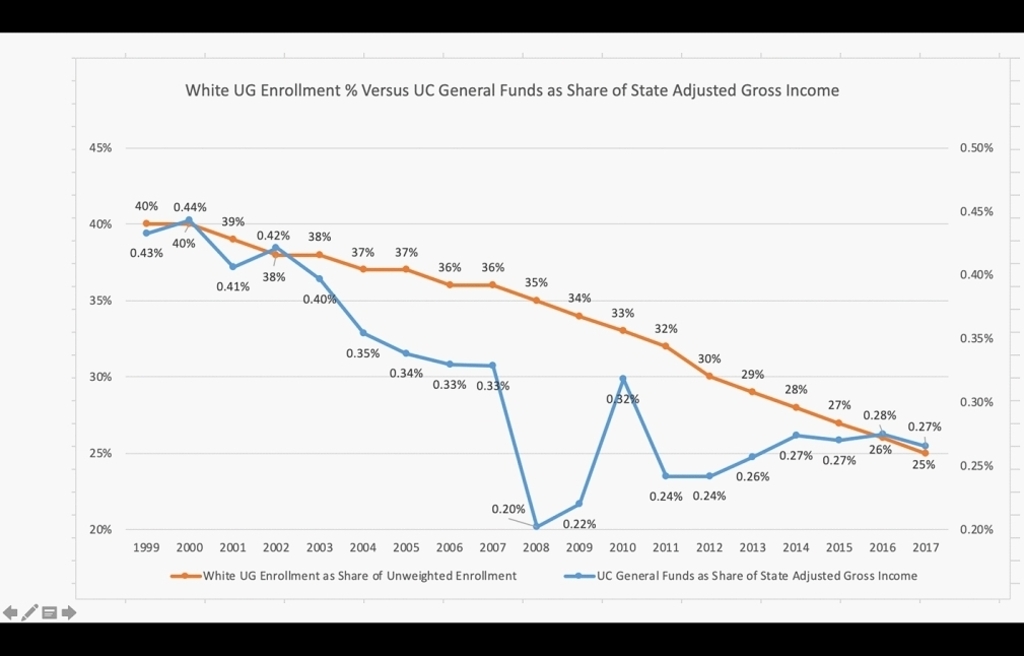

This data is already out of date: the trend of the past 15 years has been to extend resource scarcity into universities that previously had been spared. This is the story of the University of California as a whole, for instance, where the racial correlation is unmistakable. Figure 2 shows a striking correlation: the share of state income going to the University fell in near-lockstep with the share of the student body that identifies as white.

This is a textbook definition of structural racism.

The University of California resembles nearly all universities in its official dedication to access, diversity and inclusion. It is increasingly comfortable denouncing anti-Blackness and opposing racism. So this racialised defunding conflicts with higher education’s advertised goal of creating a racially inclusive form of capitalism based on knowledge, innovation and self-development rather than on exploitation, violence, segregation and war. It conflicts with the claimed outcome of equal opportunity for all university graduates regardless of race, gender, sexuality, immigration status and economic standing.

Let’s return to CUS’s contrast between the advertised and actual results of academia’s political economy. The advertised outcome is cross-racial and cross-class equality of opportunity. The actual result is cross-racial and cross-class inequality of opportunity. But as long as it looks like universities seek equality of opportunity, they are free to generate actual inequality. In the process, they rationalise that inequality as meritocratic, which makes the resulting stratification much more difficult for regular members of the society to oppose. Meanwhile, economic decision makers – central bankers, national politicians, state legislatures, business lobbyists – can retain a particularly effective means of concentrating wealth, which is to reduce the share of national product that goes to labour. This was named a while back as ‘plutonomy’, and its advances have now been well documented. It means a smaller share of overall economic returns going to labour and a larger share going to capital, which Thomas Piketty has convincingly read as capitalism returning to its historic norm of growing returns to asset ownership faster than it grows the economy or returns to wages – as enabled by the absence of active state intervention. 17 By tying wage inequality to unequal educational outcomes, universities naturalise inequality that people would otherwise be more likely to trace to economic policies – like existing taxation rates – that are openly biased against wage labour. Universities complete the mystification by concealing the linkage CUS has sought to expose, between unequal educational outcomes and unequal material resources, particularly public funding.

The role of universities in intensifying this aspect of ‘post-middle class’ inequalities in the US encapsulates the last several decades of wage and employment degradation. The period from the 1950s and 60s reflects an unusual social bargain between capital and labour. As workers became more productive during those decades, they were paid more money. Human capital theory came along to claim that they became more productive by becoming more educated. The motto was ‘learning equals earning’ – although factors such as union membership, racial exclusion and US economic dominance were arguably more important for pushing up wages for the mostly white male portion of the workforce.

This ended in the 1970s, first for blue-collar industrial workers during the deindustrialisation of what became the rust belt. Union busting is a big part of the story, offshoring is another part, and a third is race-based segmentation that allows the super-exploitation of some categories of workers, for example in the home care economy. But these methods of wage control don’t work in the same way with college graduates. How could capital apply the same methods to college students?

The university business model provides a real solution to the goal that university marketing conceals: capital accumulation can be intensified by segmenting college graduates roughly into the three groups I mentioned before. Graduates of top colleges have a good chance of entering Elite Professional Services: consulting, corporate law, banking and finance, and the like. 18 The half of college starters who don’t finish can do a lot of white-collar work from a position of employment precarity. Group III graduates are not much better off. The large group who graduate from a wide range of good but underfunded public and private colleges, Group II, who expect to enter a multi-racial middle class, get limited learning, which endows them with mid-level skills and which does not enable them to bargain effectively for high and increasing salaries. The benefit to Western capitalism (post-industrial, asset-ownership based, rent-seeking) is to shrink the entitled economic class of educated labour to about one-fifth of all university graduates, and perhaps even less.

In our default future’s fragmented, stratified condition, the university system creates a cognotariat. It Uberises knowledge work. The university itself has pioneered economic precarity for professionals in the form of the contingent faculty system, who now form the majority of college instructors. It creates high-skill people, and links high-skills to middle-level and often precarious wages. It limits entitlements like pensions and health care to specially trained and pedigreed white-collar workers, rather than spreading them widely as a sign of prosperity. If offshoring broke the wage-productivity bargain for blue-collar workers, higher education helped break it for white-collar workers. It accepted economic rule over political choices, pushed competition for scare premium places rather than egalitarian allocation of educational resources, and stratified educational quality. We talk quite a bit now about the gig economy. One of its enabling conditions is the gig academy. 19

Elements of reinvention

That’s our default future 1. As I noted, my CUS work has aimed to show that the current system isn’t muddling through towards a bit more mobility and justice, but is instead tumbling down towards generalised precarity, post-democracy, professional decline and the permanent economic vulnerability of middle-income people with university degrees. A further aim is to show how the current system emerged from deliberate policy choices that academics didn’t do enough to resist at the time, but which could still be rejected in favour of new and non-unitary structures. Escape from future 1 will require a large-scale rejection of its systemic effects and its economic model, starting with a rejection by academics.

I’ll end by pointing out two distinct but synergistic modes of building the other futures in our post-Covid reality. The more fundamental of the two is beyond my scope here: we could reject the human capital theory version of the university, which means making the business world and the government responsible for both employment and incomes. HCT was a rationale of convenience that worked for higher education during a very specific time in history. 20 It was never correct as a general theory for all graduates, and it is now serving mainly as a way for governments to shift blame for bad jobs and poor wages onto the backs of universities that are not in fact responsible for them. It is a scapegoating mechanism that prevents governments and the private sector from facing the profound flaws in their models of capitalist affluence, and requiring them to change fundamentally. Until universities can convince society to hold employers responsible for employment, UK and US universities will stay trapped in the doom loop of future 1 I’ve described.

The second way of transforming the situation would be to define the universities that those working and studying in them actually want to have. The desired features would vary by country, region, social group and discipline (it’s all quite different for bench sciences and professional schools). This means many more people actively defining the elements of reinvented universities that they think would work best. Here’s my own list:

1. Replacing equality of opportunity with equality of outcomes across racial and socioeconomic status. If general graduation rates, presence across types of profession and so on vary by group, then inequality must be addressed with policy changes and additional resources. Does your country have 21,000 academic staff yet only 140 who identify as Black? 21 You need to bulldoze complaints about too much critical race theory and set goals and mechanisms and deadlines to achieve racial proportionality.

2. Achieving equality of educational outcomes across institutional types. This isn’t a matter of TEF rankings, but of sending equal or greater funding to universities that admit more disadvantaged or underserved students until the academic results even out.

3. B.A. degrees that are debt-free. This will mean no fees and, in addition, rebuilt maintenance grants for a large percentage of students. The older members of the society should fund the educations of the younger through a progressive tax system that prevents low-income workers from subsidising high-income students.

4. B.A. degrees that reflect deep learning, which links personal identity, self-development, skills, field knowledge, and creative capabilities. This learning is labour intensive, mostly done in small groups, and expensive. Academics should articulate what this looks like in varying fields (not just learning objectives but full processes and methods), estimate its costs, and agitate for its funding. Funding for ‘limited learning’ under current conditions is completely vulnerable to cuts. 22 Academic staff and students should articulate the real thing and start forcing a triangulation with the diluted model.

5. Full funding of research, across all fields. No major problem has a solely technical solution, with Covid-19 providing a vivid example of how much we need social knowledge and public system development in addition to virology. When governments or universities fund STEM fields by sacrificing the arts, humanities and social sciences, they both discriminate against a large class of students and lower the public value of higher education. Arts and humanities fields have all but given up on asking for proper research funding, which ensures that they won’t get it. That needs to change.

6. Just employment: reduce contingent employment until part-time and unprotected academic jobs are held only by those who want them. Universities should model the ethical workplace rather than its precarious alternatives.

7. Democratised academic governance. The first six features will not exist without this. Governing boards now primarily channel political forces into universities and norm their conduct to standards set by government or industry or powerful religious or other private interests. 23 They do not now offer distinctive expertise designed to curate their academic communities that cannot already be found in those communities themselves. The same is true for the many senior managers who have taken on an adversarial relation to academic staff. Democratisation can start small but it needs to start.

These features may seem impossible. One thing I am sure of is that they are affordable. They are also possible – if and only if academics make their methods and benefits concrete, and turn them into the goals of internal university movements that, through the visible effort of their pursuit, attract outside respect and support.

Notes

-

On Hungary, see Gábor Scheiring, The Retreat of Liberal Democracy: Authoritarian Capitalism and the Accumulative State in Hungary (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). ^

-

See, for example, Cédric Durand, ‘1979 in Reverse’, Sidecar 1 June 2021, https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/1979-in-reverse; Susan Watkins, ‘Paradigm Shifts,’ New Left Review II, 127 (March/April 2021), 5–12. ^

-

William Davies, ‘The New Neoliberalism’, New Left Review II, 101 (2016), 121–34. ^

-

See, for example, Rosemary Deem and Jo-Anne Baird, ‘The English Teaching Excellence (and Student Outcomes) Framework: Intelligent Accountability in Higher Education?’, Journal of Educational Change 21:1 (2020), 215–243; Stefan Collini, ‘Universities and “Accountability”: Lessons from the UK Experience?’, in Missions of Universities: Past, Present, Future (New York: Springer, 2020), 55, 115. ^

-

See Christopher Newfield, The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), stage 5. ^

-

Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone, ‘Land-Grab Universities’, High Country News, 30 March 2020, https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.4/indigenous-affairs-education-land-grab-universities. ^

-

Davarian L. Baldwin, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities Are Plundering Our Cities (New York: Bold Type Books, 2021). ^

-

Abigail Boggs et al., ‘Abolitionist University Studies: An Invitation’, Abolition University (blog), September 2019, https://abolition.university/invitation/; Sandy Grande, ‘Refusing the University’, in Toward What Justice?: Describing Diverse Dreams of Justice in Education, eds. Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang (New York: Routledge, 2018), 47–65; la paperson, A Third University Is Possible (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017); Sharon Stein, ‘Navigating Different Theories of Change for Higher Education in Volatile Times’, Educational Studies 55:6 (November 2, 2019), 667–88. ^

-

Anon, ‘Trends in Student Aid 2020’, College Board, 11 June 2019, https://research.collegeboard.org/trends/student-aid. ^

-

On the connections among attacks on racial equality, market ideology and technology transfer, see Christopher Newfield, Unmaking the Public University: The Forty-Year Assault on the Middle Class (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008). ^

-

Sofia Mejias Pascoe, ‘UCSD Students, Faculty Push Back Against Steep Rent Hikes’, Voice of San Diego, 22 March 2021. ^

-

Joshua Clover, ‘Who Can Save the University?’, Public Books, 12 June 2017, http://www.publicbooks.org/who-can-save-the-university/. ^

-

My account here is derived from Newfield, The Great Mistake. ^

-

Anglo-American economists have long identified a large university wage premium over the wages of high school graduates, and this average premium persists. This fact does not, however, conflict with the point I’m making here about stratification within the university graduate population. Economists generally treat each education level as a homogenous cohort, which lumps together graduates of wealthy elite universities with graduates of poor local public institutions to claim a generic causal link between learning and earning. But for an acknowledgement and discussion of the growing internal inequality that I discuss here from leading proponents of this mainstream economics of education, see David Autor, Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, ‘Extending the Race between Education and Technology’, Working Paper Series (National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2020), https://doi.org/10.3386/w26705. ^

-

David Laurence, ‘Tenure in 2017: A Per Institution View’, Humanities Commons, https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:27147/ ^

-

Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, ‘Separate & Unequal’, Centre for Education and the Workforce, Georgetown University, July 2013, https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/separate-unequal/. ^

-

Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty First Century, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2014). ^

-

Lauren A. Rivera, Pedigree: How Elite Students Get Elite Jobs (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016). ^

-

Adrianna Kezar, Tom DePaola and Daniel T. Scott, The Gig Academy: Mapping Labor in the Neoliberal University (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019). ^

-

Aashish Mehta and Christopher Newfield, review of Phillip Brown, Hugh Lauder and Sin Yi, The Death of Human Capital?, in Los Angeles Review of Books, forthcoming 2021. ^

-

Richard Adams, ‘Fewer than 1% of UK University Professors Are Black, Figures Show’, The Guardian, 27 February 2020. ^

-

Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). ^

-

See Lindsay Ellis, Jack Stripling and Dan Bauman, ‘The New Order’, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 25 September 2020. ^